REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

way to cure…..

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Motor neurones are cells in the brain and spinal cord that allow us to move, speak, swallow and breathe by sending commands from the brain to the muscles that carry out these functions. Their nerve fibers are the longest in the body, a single axon can stretch from the base of the spinal cord all the way to the toes.

Motor neurons divided into either upper or lower motor neurones, forming various tightly controlled, complex circuits throughout the body. This controls both voluntary and involuntary movements through the innervation of effector muscles and glands. The upper and lower motor neurons form a two-neuron circuit.

Upper and lower motor neurons utilize different neurotransmitters to relay their signals.

Conditions that damage upper motor neurons include:

Upper motor neuron lesions prevent signals from traveling from your brain and spinal cord to your muscles. Your muscles can’t move without these signals and become stiff and weak.

Damage to upper motor neurons leads to a group of symptoms called upper motor neuron syndrome:

Muscle weakness. The weakness can range from mild to severe.

Overactive reflexes. Your muscles tense when they shouldn’t. For example, just rubbing your hand over your belly might cause your abdominal muscles to tighten up.

Tight muscles. The muscles become rigid and hard to move.

Clonus. This is muscular spasm that involve repeated, often rhythmic, contractions.

The Babinski response. Young children have a reflex called the Babinski reflex. If you stroke the bottom of their foot, their big toe will pull back and their other toes will spread out. This reflex usually disappears after age 2. In adults, the Babinski response is a sign of damage to the nervous system.

Upper motor neuron lesions can get worse over time. Over time, you can have trouble controlling your muscles.

for consultant or book an online appointment- gmail- sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Motor neuron diseases can be tricky to diagnose. Their symptoms are often very similar to those of other diseases.

Your doctor can do blood and urine tests to check for infections, muscle diseases, and other conditions that have symptoms similar to those of motor neuron diseases.

During an exam, your doctor will look for signs of a nervous system problem by checking your:

A few other tests can help your doctor diagnose upper motor neuron lesions:

MRI, or magnetic resonance imaging. It uses powerful magnets and radio waves to make pictures of structures inside your body. An MRI can show damage to upper motor neurons.

EMG, or electromyogram. It uses a thin needle to check the activity in your muscles when they contract and when they’re at rest. An EMG can check for problems with your lower motor neurons and help diagnose ALS and PLS.

Nerve conduction study. This test measures how quickly an electrical current moves through your nerve. It can show how well your nerves are sending signals to your muscles and if you have nerve damage.

Spinal tap or lumbar puncture. It removes a small amount of fluid from your spine to show whether MS or an infection is causing your symptoms.

Nerve biopsy. It removes a small sample of the nerve to check for damage. It’s not likely that you’ll have this done. Doctors hardly ever use this method when trying to diagnose an upper motor neuron disease.

Which treatment you get depends on what disease caused your upper motor neuron lesions.

Medicines won’t stop diseases like ALS or PLS, but they can help you manage symptoms. Some of the drugs used to treat upper motor neuron symptoms include:

Muscle relaxants.Baclofen, clonazepam (Klonopin), and tizanidine (Zanaflex) control muscle spasms in PLS. Doctors may also use Botox to treat tightness and stiffness of muscles.

ALS drugs. Edaravone (Radicava) and riluzole (Rilutek) slow the progression of ALS.

MS drugs. drugs which can slow MS damage to nerve cells. Beta interferons, alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), cladribine (Mavenclad), dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera), diroximel fumarate (Vumerity), fingolimod (Gilenya), glatiramer acetate (Copaxone), mitoxantrone (Novantrone), monomethyl fumarate (Bafiertam), natalizumab (Tysabri), ocrelizumab (Ocrevus), ozanimod (Zeposia), siponimod (Mayzent), teriflunomide (Aubagio)

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

An atrial septal defect (ASD) is a hole in the wall (septum) between the two upper chambers of your heart (atria). The condition is present at birth (congenital).

Small defects might be found by chance and never cause a problem. Some small atrial septal defects close during infancy or early childhood.

The hole increases the amount of blood that flows through the lungs. A large, long-standing atrial septal defect can damage your heart and lungs. Surgery or device closure might be necessary to repair atrial septal defects to prevent complications.

An atrial septal defect (ASD) is a hole in the septum, which is the muscular wall that separates the heart’s two upper chambers (atria). An ASD is a defect you are born with (congenital defect) that happens when the septum does not form properly. It is commonly called a “hole in the heart.”

A secundum ASD is a hole in the middle of the septum. The hole lets blood flow from one side of the atria to the other. The direction depends on how much pressure is in the atria.

More complicated and rare types of ASDs involve different parts of the septum and abnormal blood return from the lungs (sinus venosus) or heart valve defects (primum ASDs).

The heart is divided into four chambers, two on the right and two on the left. To pump blood throughout the body, the heart uses its left and right sides for different tasks.

The right side of the heart moves blood to the lungs. In the lungs, blood picks up oxygen then returns it to the heart’s left side. The left side of the heart then pumps the blood through the aorta and out to the rest of the body.

Doctors know that heart defects present at birth (congenital) arise from errors early in the heart’s development, but there’s often no clear cause. Genetics and environmental factors might play a role.

A large atrial septal defect can cause extra blood to overfill the lungs and overwork the right side of the heart. If not treated, the right side of the heart eventually enlarges and weakens. The blood pressure in your lungs can also increase, leading to pulmonary hypertension.

There are several types of atrial septal defects, including:

Many babies born with atrial septal defects have no signs or symptoms. Signs or symptoms can begin in adulthood.

Atrial septal defect signs and symptoms can include:

for consultant or book an online appointment- gmail- sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Atrial septal defect (ASD) occurs as the baby’s heart is developing during pregnancy. Certain health conditions or drug use during pregnancy may increase a baby’s risk of atrial septal defect or other congenital heart defect. These things include:

Some types of congenital heart defects occur in families (inherited). If you have or someone in your family has congenital heart disease, including ASD, screening by a genetic counselor can help determine the risk of certain heart defects in future children.

A small atrial septal defect might never cause any concern. Small atrial septal defects often close during infancy.

Larger atrial septal defects can cause serious complications, including:

Pulmonary hypertension can cause permanent lung damage. This complication, called Eisenmenger syndrome, usually develops over many years and occurs uncommonly in people with large atrial septal defects.

Treatment can prevent or help manage many of these complications.

If you have an atrial septal defect and are pregnant or thinking about becoming pregnant, it’s important to talk to your health care provider and to seek proper prenatal care. A health care provider may recommend ASD repair before conceiving. A large atrial septal defect or its complications can lead to a high-risk pregnancy.

Because the cause of atrial septal defect (ASD) is unclear, prevention may not be possible. But getting good prenatal care is important. If you have an ASD and are planning to become pregnant, schedule a visit with your health care provider. This visit should include:

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

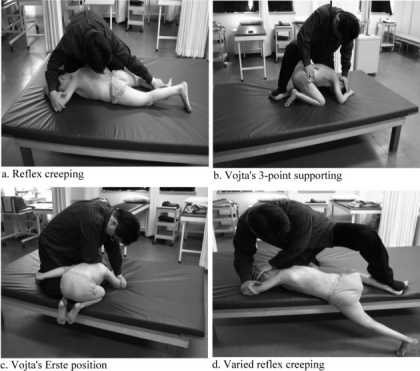

Vojta-Therapy is a dynamic neuromuscular treatment method based on the developmental kinesiology and principles of reflex locomotion. This method is supposed to treat patients with disorders of central nervous system and musculoskeletal system.

The Vojta principle was developed by child neurologist Dr Vaclav Vojta. Vojta therapy stimulates the brain, activating “innate, stored movement patterns” that are then transferred into coordinated movements of the muscles in trunk and extremities.

With repeated activation new networking within the brain and central nervous system takes place, therefore Vojta therapy has a positive influence on the entire coordination of the client and his or her spontaneous movement. As a result, improved “uprighting” against gravity, balance, gait, grasp, speech production and many other important functions can be achieved.

In Vojta Therapy, goal-directed pressure is applied to defined zones on the body while lying on the back, front or on the side. These stimuli automatically lead to two movement complexes called Reflex Rolling and Reflex Creeping.

For Vojta therapy to be most successful parents perform the treatment at home for 5-20 minutes several times a day. The therapist supports the parents and regularly reviews the treatment program and frequency of therapy according to the child’s goals and progress.

Due to the fact that Vojta therapy stimulates the brain, it directly targets the source of neurological problems like brain injuries and other neurological disorders. In Vojta therapy the musculature of the whole body is activated on a subconscious level. This is exactly the way the human body has to function when we hold ourselves upright against gravity while performing different tasks.

Reflex is an involuntary movement as a response to external stimuli. Locomotion is defined as an ability to perform a movement from one place to another. In reflex locomotion, there is a coordinated, rhythmic activation of the total skeletal musculature and a CNS response at various circuit levels.

Disturbances of posture and movement require a very complex and often a lengthy treatment, especially when they are connected with a cerebral (brain) dysfunction.

The Vojta “method”is for the physician a precious clinic tool for the evaluation of the child development from birth, and a reliable element of diagnosis; it is for the physiotherapist an efficient global therapy which can be used from the first days of life, in a preventive or curative intention.

The treatment based on the reflex locomotion contributes to:

* Modify the reflex activity of the young child and to orient the neuromotor development in a more physiological direction, by the induction of a different central neurological activity that supplies to the patient a new corporal perception. The muscular “proprioception” plays here a very important part.

* Modify the spinal automatisms in lesions of the spinal cord .

* Control the breathing in order to increase the vital capacity.

* Control the neurovegetative reactions , and promote an harmonious growth of the locomotor anatomical system .

* Prevent the orthopaedic degradation, frequent in severe pathological situations.

Comparison of reflex creeping sequences with spontaneous motor sequences of the ontogenese

| Reflex creeping (artficially provoked activity) Activity | Appearance age | Ontogenese (finalized, spontaneous activity) Appearance age |

| lateral step of the upper limb in prone position elbow support | from the birth (nape arm) (face arm) | 3 months |

| Free coordinated head rotation with symmetric vertebral axis | from the birth | 3 months |

| Lateral movements of the eyes, independent of the head posture | from the birth | end of the 1 quarter |

| One elbow support (support stabilizing synergisms) | from the birth (face arm) | middle of the 2 quarter |

| Total opening of the hand, with radial bending of the wrist , abduction of the metacarpus | from the birth (nape hand) | end of the 2 quarter |

| Coordinate differentiation of the shoulder and pelvic belts | from the birth | 6 months, rolling from dorsal to ventral |

| Activ creation of the knee support with loading | from the birth nape lower limb, variant of the ref. creeping) | quarter 3 |

| Coordinate push with the lower limb and heel support, foot in the 90° position, support on the external foot edge. | from the birth (nape lower limb) | 14 -15 months |

The application of Vojta therapies.

Vojta describes different zones that are available to stimulate the motor patterns of reflex locomotion. A light pressure on certain stimulus zone (muscles or bones) and resistance to the current movement is applied to cause patient’s involuntary motor response and performance of certain movement patterns.

The Vojta method can be divided into 2 main phases:

Reflex locomotion is activated from the three main positions:

Reflex locomotion patterns (ref.creeping and ref. rolling) are global; during these activities, the totality of the musculature is activated according to a coordinate mode. The different levels of the CNS are concerned by this activation . The reflex locomotion is provoked by specific stimulations (pressures) applied on defined zones.

Picture : Start position for the reflex creeping and general situation of the zones: The head position determines the position of the limbs, different on the face-side and the nape-side

The head position determines the position of the limbs, different on the face-side and the nape-side

The reflex creeping appears from two opposite start positions called “reciprocal positions”; each zone is therefore bilateral and the therapist has at one’s disposal access points to the afferent nervous system (proprioceptors, exteroceptors, connective tissue…) that can be used in an infinity of combinations. Defined pressure directions, are applied on one or several zones; during this stimulation, the therapist must be able to control the position of the patient, and to apply, if he wishes it, a continuous resistance to the provoked motor answering. In order to achieve this, the therapist may use different parts of his own body (abdomen, forearm, knees, etc…)

Picture : Direction of the motor answering composing the reflex creeping pattern:

The phasic movements of the limbs ( visible displacement of corporal segments) and the head rotation are conditioned by the active creation of fix points at the extremities of the “support diagonal ” (face-elbow and nape-heel); the therapist has to be very attentive to this point. The isometric motor activity of this diagonal includes a finely differentiated work of vertebral muscles and of the limbs roots .

The coordination of the antigravitic muscular activity, of the vertebral alignment, of the opposite rotation between the pelvis and shoulder belts, of the muscular contractions that radiate to extremities of the limbs, belongs to the patterns of the superior human locomotion (creeping, walking).

Picture : Pull direction of the muscular chains during the reflex creeping.

The active creation of peripheral fix points, enables the muscular organization in oblique chains that exert tractions on the bone levers according to differentiated directions. Isotonic chains have a phasic mission and determine segmental movements; isometric chainsare devoted to the stabilization and govern the emergence of the antigravitic and locomotor function. The convergence place of these muscular chains is the spine and especially the dorso-lumbar transition.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

The experienced therapist will certainly note

– that the dorso-lumbar region is frequently the place of the infantile cyphosis in neuropediatric disturbances compromising the stabilization of the vertebral axis,

– that this region is also the opposition place of the physiological double rotation in all the differentiated locomotor patterns (quadrupedic locomotion, walking)

– that the coordinate vertebral rotation is the privilege of all the fine posturo-motor functions and is cruelly missing in the totality of neurological pathologies from central origin,

– finally, that the dorso-lumbar transition is subjected, in the active human life, to many mechanical constraints which require a rigourous automatic control based on the proprioceptive information.

This enumeration underlines the interest to obtain for our patients of all ages, through the activation of precise automatic muscular games, a good corporal experience , that makes largely call in the deep sensitivity, and contributes to the elaboration, or to the restoration, of the unconscious corporal scheme.

Picture: Main muscular elements of the support diagonal during the reflex creeping

Picture: Other examples of start position: a- half-quadrupedic position called “first position”, b – lateral decubitus, phase 4 of the reflex rolling, c – lateral decubitus, phase 3 of the reflex rolling…

There are different start positions (prone position for the reflex creeping, supine or lateral for the reflex rolling etc…); therefore the therapist can choose between innumerable combinations of start positions, zones and stimulations corresponding to the same number of activation procedures for a coordinated central function.

The application of resistances against the provoked activity, transforms the phasic movement into an isometric muscular activity (without segmental displacement), whose duration can be modulated by the therapist without addiction (proprioceptive receivers). This practise leads to a temporo-spacial accumulation , then to a neuronal “overflowing” phenomenon to “force” a new neuronal itinerary. This enables, by the recruitment of new afferent ways to the CNS, the activation of possibly underexploited central territories. This technique is called pathing, it consists in provoking, then artificially maintaining , from outside, the muscular isometric contraction with the aim of soliciting a widened and coordinated activity of the CNS.

Each reflex locomotion pattern (creeping or rolling) has specific zones and can be activated from several start positions. Accessing to the same pattern from different stimulating combinations, forces the central nervous system to resort to diversified processing procedures of the afferenting flows; that means varied neuronal itineraries. These neurological procedures are to the basis of the physiological postural adaptability.

The pattern sequences ( muscular synergisms) observable during the reflex locomotion present a strict analogy with motor sequences of the normal motor development.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Human gait depends on a complex interplay of major parts of the nervous, musculoskeletal and cardiorespiratory systems.

Gait – the manner or style of walking.

Gait Analysis –

An analysis of each component of the three phases of ambulation is an essential part of the diagnosis of various neurologic disorders and the assessment of patient progress during rehabilitation and recovery from the effects of neurologic disease, a musculoskeletal injury or disease process, or amputation of a lower limb.

Gait speed

The gait cycle is a repetitive pattern involving steps and strides

A step is one single step

A stride is a whole gait cycle.

Step time – time between heel strike of one leg and heel strike of the contralateral leg.

Step width – the mediolateral space between the two feet.

The demarcation between walking and running occurs when

The sequences for walking that occur may be summarised as follows:

The normal forward step consists of two phases: stance phase; swing phase,

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Phases of the Gait Cycle (8 phase model):

Heel Strike (or initial contact) – Short period, begins the moment the foot touches the ground and is the first phase of double support.

Involves:

Foot Flat (or loading response phase)

Midstance

Heel Off

Toe Off/pre-swing

Early Swing

Mid Swing

Late Swing/declaration

Abnormal gait or a walking abnormality is when a person is unable to walk in the usual way. This may be due to injuries, underlying conditions, or problems with the legs and feet.

Walking may seems to be an uncomplicated activity. However, there are many systems of the body, such as strength, coordination, and sensation, that work together to allow a person to walk with what is considered a normal gait.

When one or more of these interacting systems is not working smoothly, it can result in abnormal gait or walking abnormality.

“Gait” means the way a person walks. Abnormal gait or gait abnormality occurs when the body systems that control the way a person walks do not function in the usual way.

This may happen due to any of the following reasons:

In some cases, gait abnormalities may clear up on their own. In other cases, an abnormal gait may be permanent. In either case, physical therapy can help improve a person’s gait and reduce any uncomfortable symptoms.

for consultant or book an online appointment- gmail- sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

At times, a person may find it difficult to walk due to an acute problem, such as a bruise, cut, or fracture. These may cause them to limp or walk differently but are not considered causes of abnormal gait.

But there are several diseases that can attack the nervous system and legs, resulting in abnormal gait. Some of the most common causes of abnormal gait include:

Abnormal gait can only officially be diagnosed by a medical professional. A doctor will likely ask a person about their medical history and symptoms and observe how they walk.

Also, a doctor may want to order additional testing, such as for neurological conditions and nerve damage.

Typically, imaging tests are used when a recent injury has occurred, to see the extent of the damage.

This is not an exhaustive list.

Musculoskeletal Causes:

Pathological gait patterns resulting from musculoskeletal are often caused by soft tissue imbalance, joint alignment or bony abnormalities affect the gait pattern as a result.

Hip Pathology

Ankle Pathologies

Footathologies

Leg length discrepancy

Antalgic Gait

for consultant or book an online appointment- gmail- sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Summary of Gait Deviations

| Observed Gait Deviation | Likely Impairement | Compensation/Mechanical Rationale |

| Hip | ||

| Backward leaning of the trunk during loading phase | Weak Hip Extensors | The line of gravity of the trunk moves behind the hips thereby reducing the need for hip extension torque |

| Forward bending of the trunk during loading response | Weak Quadriceps | The trunk is moved forward to bring the line of gravity anterior to the axis of rotation of the knee and reducing the need for knee extensors |

| Lateral trunk lean towards the stance (Compensated Trendelenburg Gait) | Marked weakness of the hip abductors Hip pain | Shifting of the trunk over the unaffected lower extremity reduces the demand of the hip abductors |

| Hip Circumduction (semicircle movement of the hip during swing phase) | Hip flexor weakness | Semicircle movement includes the combination movement of hip flexion, hip abduction and forward rotation of the pelvis |

| Knee | ||

| Flexed position of the knee during stance despite normal range of motion at the knee joint | Impairement at the ankle or the hip joint (Compensation occurring at the knee joint) | Exaggerated hip flexion or ankle dorsiflexion during stance results in flexion of the knee |

| Excessive knee flexion during swing phase | Reduced ankle dorsiflexion of the swing limb | Increase toe clearance of the swing limb. (This is accompanied with increased hip flexion) |

| Knee is kept in extension during loading phase (No extension thrust is observed) | Weak quadriceps | Anterior trunk lean is observed during early stance, thereby moving the line of gravity of the trunk slightly anterior to the axis of rotation |

| Reduced knee flexion during swing phase | Knee extension contracture | Hip hiking or hip circumduction will be observed as compensation |

| Ankle | ||

| Foot slap Quick ankle plantar flexion occurring after heel contact | Weakness in ankle dorsiflexors | None/less active dorsiflexion occurs during swing phase Normal dorsiflexion can occur during stance phase (if there is normal range of motion at the ankle joint) |

| Drop Foot Ankle remains in plantar flexion during swing phase | Weakness in ankle dorsiflexors | To prevent toes from dragging during the swing phase hip circumduction, hip hiking or exaggerated hip and knee flexion will be noted |

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Brittle bone disease is a disorder that results in fragile bones that break easily. It’s present at birth and usually develops in children who have a family history of the disease.

The disease is often referred to as osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), which means “imperfectly formed bone.”

Brittle bone disease can range from mild to severe. Most cases are mild, resulting in few bone fractures. However, the severe forms of the disease can cause:

OI can sometimes be life-threatening if it occurs in babies either before or shortly after birth. Approximately one person in 20,000 will develop brittle bone disease. It occurs equally among males and females and among ethnic groups.

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) refers to a heterogeneous group of congenital, non-sex-linked, genetic disorders of collagen type I production, involving connective tissues and bones.

The hallmark feature of OI is osteoporosis and fragile bones that fracture easily, as well as, blue sclera, dental fragility and hearing loss. These features result in reduced mobility and function to complete everyday tasks.

OI affects not only the physical but also the social and emotional well-being of children, young people, and their families. The coordinated efforts of a multidisciplinary team can support children with OI to fulfill their potential, maximizing function, independence, and well-being.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Four different genes are responsible for collagen production. Some or all of these genes can be affected in people with OI. Defective genes can produce eight types of brittle bone disease, labeled as type 1 OI through type 8 OI. The first four types are the most common. The last four are extremely rare, and most are subtypes of type 4 OI. Here are the four main types of OI:

Type 1 OI is the mildest and most common form of brittle bone disease. In this type of brittle bone disease, your body produces quality collagen but not enough of it. This results in mildly fragile bones. Children with type 1 OI typically have bone fractures due to mild traumas. Such bone fractures are much less common in adults. The teeth may also be affected, resulting in dental cracks and cavities.

Type 2 OI is the most severe form of brittle bone disease, and it can be life-threatening. In type 2 OI, your body either doesn’t produce enough collagen or produces collagen that’s poor quality. Type 2 OI can cause bone deformities. If your child is born with type 2 OI, they may have a narrowed chest, broken or misshapen ribs, or underdeveloped lungs. Babies with type 2 OI can die in the womb or shortly after birth.

Type 3 OI is also a severe form of brittle bone disease. It causes bones to break easily. In type 3 OI, your child’s body produces enough collagen but it’s poor quality. Your child’s bones can even begin to break before birth. Bone deformities are common and may get worse as your child gets older.

Type 4 OI is the most variable form of brittle bone disease because its symptoms range from mild to severe. As with type 3 OI, your body produces enough collagen but the quality is poor. Children with type 4 OI are typically born with bowed legs, although the bowing tends to lessen with age.

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) occurs because of a gene mutation (change). This mutation may be sporadic (random) or a baby may inherit the gene from one or both parents.

Some parents are carriers for the gene that causes OI. Being a carrier means you don’t have the disease yourself but can pass it down to your child.

Babies born with OI have a problem with making connective tissue due to a lack of type I collagen. Collagen is mostly found in bones, ligaments and teeth. Collagen helps keep bones strong. As a result of the gene mutation, the body may not make enough collagen, and bones may weaken.

The estimated incidence is approximately 1 in every 12,000-15,000 births. OI occurs with equal frequency among males and females and across races and ethnic groups. The lifespan varies with the type.

A fundamental pathology in OI is a disturbance in the synthesis of type I collagen, which is the predominant protein of the extracellular matrix of most tissues. In bone, this defect results in osteoporosis, thus increasing the tendency to fracture. Besides bone, type I collagen is also a major constituent of dentine, sclerae, ligaments, blood vessels and skin.

The symptoms of brittle bone disease differ according to the type of the disease. Everyone with brittle bone disease has fragile bones, but the severity varies from person to person. Brittle bone disease has one or more of the following symptoms:

for consultant or book an online appointment- gmail- sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Your doctor can diagnose brittle bone disease by taking X-rays. X-rays allow your doctor to see current and past broken bones. They also make it easier to view defects in the bones. Lab tests may be used to analyze the structure of your child’s collagen. In some cases, your doctor may want to do a skin punch biopsy. During this biopsy, the doctor will use a sharp, hollow tube to remove a small sample of your tissue.

Genetic testing can be done to trace the source of any defective genes.

The main goal of treatment is to prevent deformities and fractures. And, once your child gets older, to allow him or her to function as independently as possible.

Management options include:

Varied across the diverse spectrum of the disease.

Complications may affect most body systems in a baby or child with OI. The risk of developing complications depends on the type and severity of your baby’s OI. Complications may include the following:

Physical and occupational therapy are part of an interdisciplinary approach to treatment. The medical team may also include a primary care physician, orthopedist, geneticist, nutritionist, social worker, and psychologist. Children and adults with OI, especially those with spine curves which may affect pulmonary status, may regularly see a pulmonologist. Ideally planning ahead for rehabilitation is included in the preparation for surgery.

Depending on the OI type, many people can live a high quality of life with osteogenesis. People with OI can improve bone health by:

Life expectancy varies greatly depending on OI type. Babies with Type II often die soon after birth. Children with Type III may live longer, but often only until around age 10. They may also have severe physical deformities.

People with Type IV generally live into adulthood but may have a slightly shortened lifespan. People with Type I generally have a typical lifespan.

When working with individuals and families living with OI, therapists should keep these principles in mind:

Maximizing a person’s strength and function not only improves overall health and wellbeing, but also improves bone health, as mechanical stresses and muscle tension on bone help increase bone density. eg, deformities such as a flattened skull, a lordotic back, or tight hip flexor muscles can be prevented or minimized through therapy.

Approaches include:

Circumstances requiring intermittent or long-term physical therapy:

Key Principles of Therapeutic Strategies

Patience and task analysis are both necessary to develop a successful therapy program. Developmental concepts and specific skills need to be analyzed closely, so that many small improvements can lead to achieving a particular therapy goal.

Key therapeutic strategies include the following:

1. Skill Progression – before learning personal care skills, a child must first develop gross motor skills eg reaching and sitting, which may be delayed or difficult for those with moderate to severe OI; Adults may need to relearn a series of skills after a serious injury.

2. Protective handling, preventive positioning, and active movement with gradual progression (contribute to safe development of motor skills).

3. Water therapy – provides the opportunity for children with OI to develop skills in a reduced gravity environment before trying them on land. Adults often use water therapy to relearn or maintain motor skills. Water is a great place to start getting past the fear of movement.

4. Equipment – ranging from simple pillows to specialized wheelchairs, can help children and adults achieve motor and personal care goals even if they have weakness or are recovering from a fracture.

5. Encouraging healthy living is an important part of the therapeutic relationship. Promoting general health, preventing obesity, and encouraging participation in recreational activities are important elements of achieving the goal of a lifestyle of wellness and greater independence.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Heterotopic ossification is frequently observed in the rehabilitation population. It consists of the formation of mature, lamellar bone in extraskeletal soft tissue where bone does not usually exist. Patient populations at risk of developing heterotopic ossification include patients with burns, strokes, spinal cord injuries, traumatic amputations, joint replacements, and traumatic brain injuries.

HO only occurs below the level of injury. The specific cause of HO after spinal cord injury is unknown. There are many theories about why it develops after spinal cord injury including:

HO may develop within days following the spinal cord injury or several months later. HO usually occurs 3-12 weeks after spinal cord injury yet has been known to also develop years later.

HO occurs after other injuries, too. HO has been known to occur in cases of traumatic brain injury, stroke, poliomyelitis, myelodysplasia, carbon monoxide poisoning, spinal cord tumors, syringomyelia, tetanus, multiple sclerosis, post total hip replacements, post joint arthroplasty, and after severe burns.

In patients with spinal cord injury, 90% of cases occur in hips but it can also occur at the knees, elbows and shoulders. HO occurs more in men than in women. People in their 20’s and 30’s are affected more than other age groups.

Subtypes

The initial inflammatory phase of HO may mimic other pathologies such as cellulitis, thrombophlebitis, osteomyelitis, or a tumorous process.

Other differential diagnoses include DVT, septic arthritis, hematoma, or fracture. DVT and HO have been positively associated. This is thought to be due to the mass effect and local inflammation of the HO, encouraging thrombus formation. The thrombus formation is caused by venous compression and phlebitis.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

The most common conditions found in conjunction with heterotopic ossification:

Because the cause of HO is currently unknown, preventive measures are limited. Some doctors will prescribe medications to prevent bone growth. The blood thinner Coumadin (Warfarin) is sometimes prescribed because it decreases the activity of Vitamin K, an important component in the development of bone. Another type of medication often prescribed is non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDS) drugs. These medications prevent formation of bone growth by blocking prostaglandin cells from forming bone. Depending on your individual health and needs, your doctor and team will develop a plan that is right for you. All medications come with side effects – never start or stop a medication without consulting with your doctor first.

People with SCI need to be aware of changes in sensation, function, pain and strength. With any change, speak with your doctor and report changes early. Losing function, movement or having pain can indicate problems like HO. Be proactive in your health and talk with your doctor about any changes you experience.

Current treatment recommendations consist of mobilization with ROM exercises, indomethacin, etidronate, and surgical resection.

The two types of medications shown to have both prophylactic and treatment benefits are as follows:

The two main goals of surgical intervention are to

Rehabilitation Post-Operatively: It is recommended that a rehabilitation program should start within the first 24 hours after surgery. The program should last for 3 weeks to prevent adhesion.

Complications of HO present itself through decreased function and mobility, peripheral nerve entrapment, and pressure ulcers.

In the case of sporting MO, usually athletes are able to progress to light activity at 2 to 3 months, full activity by 6 months, and back to their preinjury level by 1 year.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Physical therapy has been shown to benefit patients suffering from heterotopic ossification. Pre-operative PT can be used to help preseve the structures around the lesion. ROM exercises (PROM, AAROM, AROM) and strengthening will help prevent muscle atrophy and preserve joint motion.

Clinical note: caution must be taken when working with patients with known heterotopic lesions. Therapy which is too aggressive can aggravate the condition and lead to inflammation, erythema, hemorrhage, and increased pain.

Post-operative rehabilitation has also shown to benefit patients with recent surgical resection of heterotopic ossification. The post-op management of HO is similar to pre-op treatment but much more emphasis is placed on edema control, scar management, and infection prevention. Calandruccio et al. outlined a rehabilitation protocol for patients who underwent surgical excision of heterotopic ossification of the elbow. The phases of rehab and goals for each phase are as follows:

Phase I(Week 1) Heterotopic ossification of the elbow

Goals:

Phase II(2-8 weeks)

Goals:

Phase III (9-24 weeks)

Goals:

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Cervical cancer develops in a woman’s cervix (the entrance to the uterus from the vagina).

Almost all cervical cancer cases (99%) are linked to infection with high-risk human papillomaviruses (HPV), an extremely common virus transmitted through sexual contact.

Although most infections with HPV resolve spontaneously and cause no symptoms, persistent infection can cause cervical cancer in women.

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women. In 2018, an estimated 570 000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer worldwide and about 311 000 women died from the disease.

Effective primary (HPV vaccination) and secondary prevention approaches (screening for, and treating precancerous lesions) will prevent most cervical cancer cases.

When diagnosed, cervical cancer is one of the most successfully treatable forms of cancer, as long as it is detected early and managed effectively. Cancers diagnosed in late stages can also be controlled with appropriate treatment and palliative care.

With a comprehensive approach to prevent, screen and treat, cervical cancer can be eliminated as a public health problem within a generation.

Cervical cancer is a type of cancer that occurs in the cells of the cervix — the lower part of the uterus that connects to the vagina.

Various strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV), a sexually transmitted infection, play a role in causing most cervical cancer.

When exposed to HPV, the body’s immune system typically prevents the virus from doing harm. In a small percentage of people, however, the virus survives for years, contributing to the process that causes some cervical cells to become cancer cells.

You can reduce your risk of developing cervical cancer by having screening tests and receiving a vaccine that protects against HPV infection.

Early-stage cervical cancer generally produces no signs or symptoms.

Signs and symptoms of more-advanced cervical cancer include:

Cervical cancer begins when healthy cells in the cervix develop changes (mutations) in their DNA. A cell’s DNA contains the instructions that tell a cell what to do.

Healthy cells grow and multiply at a set rate, eventually dying at a set time. The mutations tell the cells to grow and multiply out of control, and they don’t die. The accumulating abnormal cells form a mass (tumor). Cancer cells invade nearby tissues and can break off from a tumor to spread (metastasize) elsewhere in the body.

It isn’t clear what causes cervical cancer, but it’s certain that HPV plays a role. HPV is very common, and most people with the virus never develop cancer. This means other factors — such as your environment or your lifestyle choices — also determine whether you’ll develop cervical cancer.

The type of cervical cancer that you have helps determine your prognosis and treatment. The main types of cervical cancer are:

Sometimes, both types of cells are involved in cervical cancer. Very rarely, cancer occurs in other cells in the cervix.

Risk factors for cervical cancer include:

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

To reduce your risk of cervical cancer:

Have routine Pap tests. Pap tests can detect precancerous conditions of the cervix, so they can be monitored or treated in order to prevent cervical cancer. Most medical organizations suggest beginning routine Pap tests at age 21 and repeating them every few years.

Practice safe sex. Reduce your risk of cervical cancer by taking measures to prevent sexually transmitted infections, such as using a condom every time you have sex and limiting the number of sexual partners you have.

A Pap smear is a test doctors use to diagnose cervical cancer. To perform this test, your doctor collects a sample of cells from the surface of your cervix. These cells are then sent to a lab to be tested for precancerous or cancerous changes.

If these changes are found, your doctor may suggest a colposcopy, a procedure for examining your cervix. During this test, your doctor might take a biopsy, which is a sample of cervical cells.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)recommends the following screening schedule for women by age:

Ages 30 to 65: Get a Pap smear once every three years, get a high-risk HPV (hrHPV) test every five years, or get a Pap smear plus hrHPV test every five years.

For cervical cancer that’s caught in the early stages, when it’s still confined to the cervix, the five-year survival rate is 92 percent

Here are some key statistics about cervical cancer.

The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2019, approximately 13,170 American women will be diagnosed with cervical cancer and 4,250 will die from the disease. Most cases will be diagnosed in women between the ages of 35 and 44.

Hispanic women are the most likely ethnic group to get cervical cancer in the United States. American Indians and Alaskan natives have the lowest rates.

The death rate from cervical cancer has dropped over the years. From 2002-2016, the number of deaths was 2.3 per 100,000 womenper year. In part, this decline was due to improved screening.

It’s rare to get diagnosed with cervical cancer while you’re pregnant, but it can happen. Most cancers found during pregnancy are discovered at an early stage.

Treating cancer while you’re pregnant can be complicated. Your doctor can help you decide on a treatment based on the stage of your cancer and how far along you’re in your pregnancy.

If the cancer is at a very early stage, you may be able to wait to deliver before starting treatment. For a case of more advanced cancer where treatment requires a hysterectomy or radiation, you’ll need to decide whether to continue the pregnancy.

Doctors will try to deliver your baby as soon as it can survive outside the womb.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

The prerequisite for any treatment in the shoulder region of a patient with pain is a precise and comprehensive picture of the signs and symptoms as they occur during the assessment and as they existed until then. Because of its many structures (most of which are in a small area), its many movements, and the many lesions that may occur either inside or outside the joints, the shoulder complex is difficult to assess. Having a systematic and structured approach to the shoulder history and examination ensures that key aspects of the condition are elicited and important conditions are not missed. Information gathered in this process can help guide decisions about the need for special tests or investigations and ongoing management.

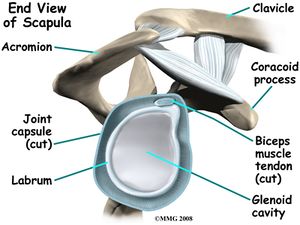

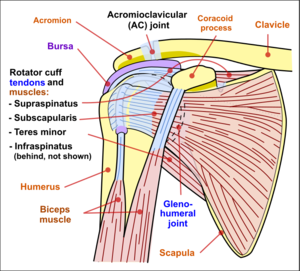

The range of motion (ROM) of the arm relative to the trunk does not just come from the glenohumeral joint. Movement also occurs in the acromioclavicular (a.c.) joint, sternoclavicular (s.c.) joint and the upper costosternal and costovertebral joints. Another prerequisite for normal movement is that the scapula should be able to move freely, relative from the dorsal thorax wall.

The glenohumeral joint is a multiaxial, ball-and-socket, synovial joint with a relatively shallow socket: the cavitas glenoidalis. The joint depends primarily on the muscles and ligaments for its support, stability and integrity. The ring of firbocartilage, labrum, surrounds and deepens the glenoid cavity of the scapula about 50%.

Stability is mostly offered by the periarticular muscles, that originate from the scapula and insert on the caput humeri. This rotator cuff includes the m.supraspinatus, m. infraspinatus and m. subscapularis. The spina scapulae is a bony ridge on the dorsal side and is the insertion location of the m. trapezius and m. deltoideus. The spina scapulae broadens on the lateral side, shaping the acromion. The space between the acromion and humerus head is called the subacromial space. In this space you’ll find the tendons of the rotators and the bursa subacromialis (= bursa subdeltoidea). The tuberculum minus and tuberculum majus are divided by the sulcus intertubercularis, where the tendon of the caput longum m. biceps brachii runs. This tendon continues into into the joint and has its insertion on the top ridge of the cavitas glenoidalis (labrum glenoidale).

Injuries in and around the shoulder usually give pain in the (upper)arm and sometimes in the area of the m. trapezius, dermatomes C4 and C5. Referred pain from the shoulder is mostly indicated by the patient in the C5 dermatome, pain from the clavicula, a.c. joint and/ or sc. joints are felt in C4.

Asking about the mechanism of any specific injury is critical, particularly about three factors relating to the time of injury: anatomical site, limb position and subjective experiences. Take care to clarify the patient’s description of the anatomical site. A description of the arm position at the time of the injury is also valuable. For example, falling on an abducted and externally rotated arm increases the risk of shoulder dislocation or subluxation. Finally, exploring the subjective experiences of the patient at the time of injury can be useful. For example, a snapping or cracking sound may be related to a bone or ligament breaking; feeling something ‘pop out’ may suggest a joint dislocation or subluxation.

The cervical spine can refer pain to the shoulder/scapular region. It is imperative that the cervical spine be screened appropriately as it may be contributing to the patient’s clinical presentation.

The key principle with this phase of the shoulder examination is symmetry. The shape, position and function of each shoulder should be relatively similar. Some differences can occur due to shoulder dominance; the dominant shoulder may sit lower and may appear somewhat larger due to larger muscle mass. Also look at position of scapula and or winging and any abnormal postures of swellings/injuries.

Palpation of the shoulder region may provider the physical therapist with valuable information. The physical therapist should note the presence of swelling, texture, and temperature of the tissue. Additionally the physical therapist may observe asymmetry, sensation differences, and pain reproduction. Key palpable structures include:

A comprehensive neurological examination may be warranted in patients that present with a primary complaint of shoulder pain. The presence of neurological symptoms including numbness and tingling may warrant this examination.

The patient performs active movements in all functional planes for the shoulder. This includes flexion, extension, abduction, adduction and internal and external rotation. Estimate the range of movement or measure with a goniometer and compare the affected with the unaffected shoulder and with the normal expected range.

| Active movements of the shoulder complex | ROM |

|---|---|

| Elevation through abduction | 170°-180° |

| Elevation through forward flexion | 160°-180° |

| Elevation through the plane of the scapula | 170°-180° |

| Lateral (external) rotation | 80°-90° |

| Medial (internal) rotation | 60°-100° |

| Extension | 50°-60° |

| Adduction | 50°-75° |

| Horizontal adduction/abduction (cross-flexion/ cross-extension) | 130° |

| Circumduction | 200° |

| Scapular protraction | |

| Scapular retration | |

| Combined movements (if necessary) | |

| Repetitive movements (if necessary) | |

| Sustained positions (if necessary) |

Dysfunction – affecting movements. Which movements are limited, as this can help isolate the problem.

Consider the following if movements are limited by:

May include each of the motions stated in the active ROM section. The therapist may opt to include overpressure to further stress the joint.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Assessment of the flexibility of certain muscles may be warranted in patients with shoulder pain. These muscles may include, but are not limited to:

Resistive testing of the shoulder muscles typically includes the following motions:

Resistive testing of the scapular stabilisation muscles may include:

Assessment of the mobility of the joint may indicate hypomobility within the joint and/or reproduce symptoms.

Several special tests exist for particular disorders of the shoulder. Below are links to the specific pages for each pathology that describe the special tests:

Patients with shoulder pain should be questioned for the presence of red or yellow flags. A thorough medical history and possibly the use of a medical screening form is the initial step in the screening process. The chart below highlights some of the most common red flag conditions for patients with shoulder pain.

Determine if patient’s symptoms are reflective of a visceral disorder or a serious potential life-threatening illness such as cancer, visceral pathology or fracture.

To assess for yellow flags, if suspected these tools may be used;

Fractures Fractures may result from trauma such as falls onto an outstretched hand. These are known as FOOSH injuries. Commonly fractured within the shoulder region are:

Diagnostic Imaging Radiographs of the shoulder can be used to identify cysts, sclerosis, or acromial spurs, osteoarthritis of the acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joint, or calcific tendonitis. Common radiographic views may include (this may vary depending on medical provider):

Presentation of different shoulder pathologies

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com