REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Sjogren’s (SHOW-grins) syndrome is a disorder of your immune system identified by its two most common symptoms — dry eyes and a dry mouth.

The condition often accompanies other immune system disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. In Sjogren’s syndrome, the mucous membranes and moisture-secreting glands of your eyes and mouth are usually affected first — resulting in decreased tears and saliva.

Although you can develop Sjogren’s syndrome at any age, most people are older than 40 at the time of diagnosis. The condition is much more common in women. Treatment focuses on relieving symptoms.

epidemiology

Internationally, comparative studies between different ethnic groups have suggested that Sjögren syndrome is a homogeneous disease that occurs worldwide with similar prevalence and affects 1-2 million people.

The female-to-male ratio of Sjögren syndrome is 9:1. Sjögren syndrome can affect individuals of any age but is most common in elderly people. Onset typically occurs in the fourth to fifth decade of life.

Symptoms

The two main symptoms of Sjogren’s syndrome are:

- Dry eyes. Your eyes might burn, itch or feel gritty — as if there’s sand in them.

- Dry mouth. Your mouth might feel like it’s full of cotton, making it difficult to swallow or speak.

Some people with Sjogren’s syndrome also have one or more of the following:

- Joint pain, swelling and stiffness

- Swollen salivary glands — particularly the set located behind your jaw and in front of your ears

- Skin rashes or dry skin

- Vaginal dryness

- Persistent dry cough

- Prolonged fatigue

Causes

Sjogren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disorder. Your immune system mistakenly attacks your body’s own cells and tissues.

Scientists aren’t certain why some people develop Sjogren’s syndrome. Certain genes put people at higher risk of the disorder, but it appears that a triggering mechanism — such as infection with a particular virus or strain of bacteria — is also necessary.

In Sjogren’s syndrome, your immune system first targets the glands that make tears and saliva. But it can also damage other parts of your body, such as:

- Joints

- Thyroid

- Kidneys

- Liver

- Lungs

- Skin

- Nerves

Prognosis

Sjögren syndrome carries a generally good prognosis. In patients who develop a disorder associated with Sjögren syndrome, the prognosis is more closely related to the associated disorder (eg, SLE, lymphoma). Interestingly, primary Sjögren syndrome is associated with lower cardiovascular risk factors and lower risk of serious cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction and stroke, in comparison with SLE.

Although salivary and lacrimal function generally stabilize, the presence of SSA and/or hypocomplementemia may predict a decline in function.

Morbidity and mortality

Morbidity associated with Sjögren syndrome is mainly associated with the gradually decreased function of exocrine organs, which become infiltrated with lymphocytes. The increased mortality rate associated with the condition is primarily related to disorders commonly associated with Sjögren syndrome, such as SLE, RA, and primary biliary cirrhosis. Patients with primary Sjögren syndrome who do not develop a lymphoproliferative disorder have a normal life expectancy.

Risk factors

Sjogren’s syndrome typically occurs in people with one or more known risk factors, including:

- Age. Sjogren’s syndrome is usually diagnosed in people older than 40.

- Sex. Women are much more likely to have Sjogren’s syndrome.

- Rheumatic disease. It’s common for people who have Sjogren’s syndrome to also have a rheumatic disease — such as rheumatoid arthritis or lupus.

Complications

The most common complications of Sjogren’s syndrome involve your eyes and mouth.

- Dental cavities. Because saliva helps protect the teeth from the bacteria that cause cavities, you’re more prone to developing cavities if your mouth is dry.

- Yeast infections. People with Sjogren’s syndrome are much more likely to develop oral thrush, a yeast infection in the mouth.

- Vision problems. Dry eyes can lead to light sensitivity, blurred vision and corneal damage.

Less common complications might affect:

- Lungs, kidneys or liver. Inflammation can cause pneumonia, bronchitis or other problems in your lungs; lead to problems with kidney function; and cause hepatitis or cirrhosis in your liver.

- Lymph nodes. A small percentage of people with Sjogren’s syndrome develop cancer of the lymph nodes (lymphoma).

- Nerves. You might develop numbness, tingling and burning in your hands and feet (peripheral neuropathy).

History

The clinical presentation of Sjögren syndrome may vary. Most patients are women, and onset is usually at age 40-60 years, but the syndrome also can affect men and children. The onset is insidious. The first symptoms in primary Sjögren syndrome can be easily overlooked or misinterpreted, and diagnosis can be delayed for as long as several years.

Xerophthalmia (dry eyes) and xerostomia (dry mouth) are the main clinical presentations in adults. Bilateral parotid swelling is the most common sign of onset in children.

Extraglandular involvement in Sjögren syndrome falls into two general categories: periepithelial infiltrative processes and extraepithelial extraglandular involvement. Periepithelial infiltrative processes include interstitial nephritis, liver involvement, and bronchiolitis and generally follow a benign course.

Extraepithelial extraglandular involvement in Sjögren syndrome is related to B-cell hyperreactivity, hypergammaglobulinemia, and immune complex formation and includes palpable purpura, glomerulonephritis, and peripheral neuropathy. These latter manifestations occur later in the course of Sjögren syndrome and are associated with a higher risk of transformation to lymphoma.

Symptoms of Sjögren syndrome can decrease the patient’s quality of life in terms of its physical, psychological, and social aspects.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Sicca symptoms (dry eyes and dry mouth)

Although dry eyes and dry mouth are the most common symptoms in patients with Sjögren syndrome, most patients who report these symptoms have other underlying causes. The incidence of sicca symptoms increases with age. Indeed, more than one third of elderly persons have sicca symptoms. Whether this is part of the normal aging process (associated with fibrosis and atrophy observed on some lip biopsy studies) or is due to the accumulation of associated illnesses and medications is unclear.

Common medications that can cause sicca symptoms in any age group include antidepressants, anticholinergics, beta blockers, diuretics, and antihistamines. Anxiety can also lead to sicca symptoms. Women who use hormone replacement therapy may be at increased risk of dry eye syndrome.

Patients may describe the effects dry mouth in the following ways:

- Inability to eat dry food (eg, crackers) because it sticks to the roof the mouth

- Tongue sticking to the roof of the mouth

- Putting a glass of water on the bed stand to drink at night (and resulting nocturia)

- Difficulty speaking for long periods of time or the development of hoarseness

- Higher incidence of dental caries and periodontal disease

- Altered sense of taste

- Difficulty wearing dentures

- Development of oral candidiasis with angular cheilitis, which can cause mouth pain

Dry eyes may be described as red, itchy, and painful. However, the most common complaint is that of a gritty or sandy sensation in the eyes. Symptoms typically worsen throughout the day, probably due to evaporation of the already scanty aqueous layer. Some patients awaken with matting in their eyes and, when severe, have difficulty opening their eyes in the morning. Blepharitis can also cause similar morning symptoms.

Parotitis

Patients with Sjögren syndrome may have a history of recurrent parotitis, often bilateral. Although in some patients the parotid glands become so large that the patients report this as a problem, more often the examining physician discovers them.

Cutaneous symptoms

Nonvasculitic cutaneous manifestations in Sjögren syndrome include the following :

- Dryness

- Eyelid dermatitis

- Pruritus

- Erythema annulare

Cutaneous vasculitis, such as palpable purpura, develops in some patients with Sjögren syndrome, especially those with hypergammaglobulinemia or cryoglobulinemia. Raynaud phenomenon is observed in approximately 20% of patients.

Pulmonary symptoms

Patients with Sjögren syndrome can develop dryness of the tracheobronchial mucosa (xerotrachea), which can manifest as a dry cough. Less often, patients develop dyspnea from an interstitial lung disease that is typically mild. Patients may develop recurrent bronchitis or even pneumonitis (infectious or noninfectious).

Gastrointestinal symptoms

Dryness of the pharynx and esophagus frequently leads to difficulty with swallowing (deglutition), in which case patients usually describe food becoming stuck in the upper throat. Lack of saliva may lead to impaired clearance of acid and may result in gastroesophageal reflux and esophagitis.

Abdominal pain and diarrhea can occur. Rarely, patients develop acute or chronic pancreatitis, as well as malabsorption due to pancreatic insufficiency. However, caution is advised when interpreting laboratory results because an elevated amylase level may arise from the parotid gland.

Patients with gastritis should be tested for Helicobacter pylori infection, because of its association with gastric mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas.

Patients with Sjögren syndrome are at increased risk for delayed gastric emptying, which can cause early satiety, upper abdominal discomfort, nausea, and vomiting.

Cardiac symptoms

Pericarditis and pulmonary hypertension, with their attendant symptomatology, can occur in Sjögren syndrome. Orthostatic symptoms related to dysfunction of autonomic control of blood pressure and heart rate is associated with increased severity of Sjögren syndrome.

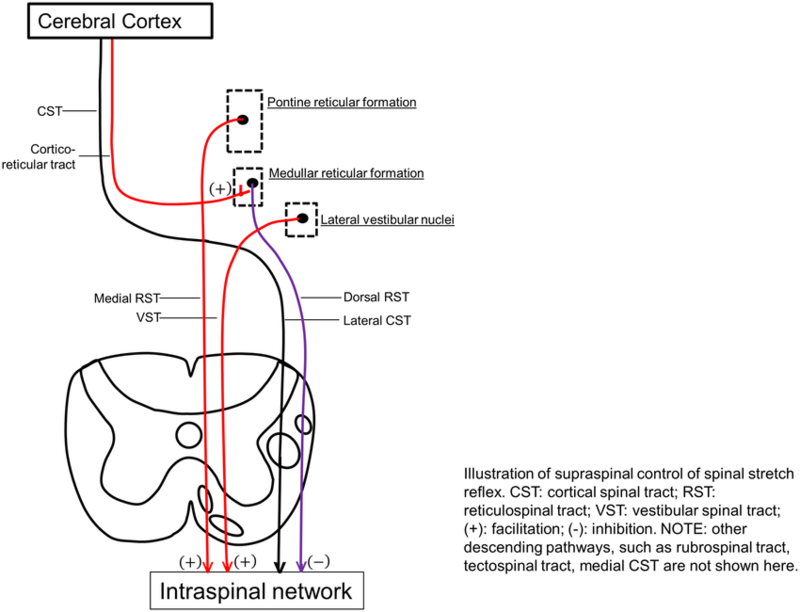

Neurologic symptoms

The occurrence of central nervous system (CNS) and spinal cord involvement in Sjögren syndrome is estimated by various studies to be 8-40%, with manifestations including myelopathy, optic neuropathy, seizures, cognitive dysfunction, and encephalopathy. Attempts must be made to distinguish other causes of these symptoms, including concomitant SLE, multiple sclerosis, cerebrovascular disease, and Alzheimer disease.

Sensory, motor, or sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy, often subclinical, can be detected in up to 55% of unselected patients with Sjögren syndrome. Symptoms of distal paresthesias may be present. Cranial neuropathies can develop, particularly trigeminal neuropathy or facial nerve palsy. Mononeuritis multiplex should prompt a search for a vasculitis.

Progressive weakness and paralysis secondary to hypokalemia due to underlying renal tubular acidosis can occur and is potentially treatable.

Renal symptoms

Renal calculi, renal tubular acidosis, and osteomalacia, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, and hypokalemia can occur secondary to tubular damage caused by interstitial nephritis, the most common form of renal involvement in Sjögren syndrome.

Interstitial cystitis, with symptoms of dysuria, frequency, urgency, and nocturia, is strongly associated with Sjögren syndrome.

Glomerulonephritis can be caused by Sjögren syndrome but is uncommon and is usually attributable to another disorder, such as SLE or mixed cryoglobulinemia.

Additional symptoms

Nasal dryness can result in discomfort and bleeding. Women may also have a dry vagina, which can lead to dyspareunia, vaginitis, and pruritus.

Patients with Sjögren syndrome may report fatigue, joint pain, and, sometimes, joint swelling. A careful review of systems must be performed to differentiate these from the manifestations of other disorders (see DDx). Fibromyalgia is common in patients with Sjögren syndrome, with a prevalence of about 31%.

Women with Sjögren syndrome may have a history of recurrent miscarriages or stillbirths, and women and men may have a history of venous or arterial thrombosis. These are related to the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (eg, lupus anticoagulant or anticardiolipin antibodies).

Secondary Sjogren syndrome

Secondary Sjögren syndrome appears late in the course of the primary disease. However, in some patients, primary Sjögren syndrome may precede SLE by many years. Secondary Sjögren syndrome is usually mild, and sicca symptoms are the main feature. Unlike patients with primary Sjögren syndrome, persons with the secondary type have significantly fewer systemic manifestations. These manifestations include the following:

- Salivary gland swelling

- Lung involvement

- Nervous system involvement

- Renal involvement

- Raynaud phenomenon

- Lymphoproliferative disorders

In secondary Sjögren syndrome, symptoms of the primary disease predominate. Secondary Sjögren syndrome does not modify the prognosis or outcome of the basic disease. Polyarteritis nodosa and Sjögren syndrome may also coexist, perhaps best viewed as an overlap syndrome.

Approach Considerations

No curative agents for Sjögren syndrome exist. The treatment of the disorder is essentially symptomatic.

Skin and vaginal dryness

Patients should use skin creams, such as Eucerin, or skin lotions, such as Lubriderm, to help with dry skin. Vaginal lubricants, such as Replens, can be used for vaginal dryness. Vaginal estrogen creams can be considered in postmenopausal women. Watch for and treat vaginal yeast infections.

Arthralgias and arthritis

Acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be taken for arthralgias. Consider hydroxychloroquine if NSAIDs are not sufficient for the synovitis occasionally associated with primary Sjögren syndrome. However, hydroxychloroquine does not relieve sicca symptoms. Patients with RA associated with Sjögren syndrome likely require other disease-modifying agents.

Additional treatment considerations

In patients with major organ involvement, such as lymphocytic interstitial lung disease, consider therapy with steroids and immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclophosphamide.

While cyclophosphamide and similar agents may be helpful for treating serious manifestations of Sjögren syndrome or disorders associated with Sjögren syndrome, clinicians should understand that these agents are also associated with the development of lymphomas.

Long-term anticoagulation may be needed in patients with vascular thrombosis related to antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

In a small group of patients with primary Sjögren syndrome, mycophenolate sodium reduced subjective, but not objective, ocular dryness and significantly reduced hypergammaglobulinemia and RF.

Among the biologic therapies, the greatest experience in primary Sjögren syndrome is with rituximab, an anti-CD20 (which is expressed on B-cell precursors) monoclonal antibody. Anti-B–cell strategies, particularly rituximab, have a promising effect in the treatment of patients with severe extraglandular manifestations of Sjögren syndrome.

Reports on the use of rituximab in patients with primary Sjögren syndrome have emerged in the literature. In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, Meijer et al found that rituximab significantly improved saliva flow rate, lacrimal gland function, and other variables in patients with primary Sjögren syndrome.

In an open-label clinical trial, modest improvements were noted in patient-reported symptoms of fatigue and oral dryness. However, no significant improvement in the objective measures of lacrimal and salivary gland function was noted, despite effective depletion of blood B cells. In a randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of 120 patients with primary Sjögren syndrome, treatment with rituximab did not alleviate disease activity or symptoms at week 24, although it did alleviate some symptoms at weeks 6 and 16.

Rituximab appears promising in the treatment of vasculitis and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)–dependent ataxic neuropathy. Results from the AIR registry (French) indicated that rituximab appears to be effective in cryoglobulinemia or vasculitis-related peripheral nervous system involvement in primary Sjögren syndrome.

In a prospective study of 78 patients with primary Sjögren syndrome treated with rituximab, significant improvement in extraglandular manifestations was reported, as measured by EULAR [European League Against Rheumatism] Sjögren Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI) (disease activity score) and overall good tolerance reported. Several smaller studies of rituximab revealed improvement of arthralgias, regression of parotid gland swelling, and improvement of immune-related thrombocytopenia.

Of the TNF inhibitors, both etanercept and infliximab have failed to demonstrate significant benefit in Sjögren syndrome.

Combination therapy with leflunomide and hydroxychloroquine resulted in a significant decrease in ESSDAI scores and caused no serious adverse events, in a small phase 2a randomized clinical trial from the Netherlands. At 24 weeks, the mean difference in ESSDAI score in the leflunomide-hydroxychloroquine group (n=21), compared with the placebo group (n=7), was –4.35 points after adjustment for baseline values.

Fewer data are available with regard to the role of anti-CD22, anti-BAFF, anti-IL-1, type 1 interferon, and anti-T–cell agents in treatment of primary Sjögren syndrome, with further investigations ongoing. The overall paucity of evidence in therapeutic studies in primary Sjögren syndrome suggests that much larger trials of the most promising therapies are necessary. The investigators concluded that further evaluation of leflunomide–hydroxychloroquine combination therapy in larger clinical trials is warranted.

Emergency department care

The diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome can be made from the ED if the index of suspicion is high. Patients may present with mild symptoms (eg, eye grittiness, eye dryness or discomfort, dry mouth, recurrent caries). Bilateral parotid gland swelling is also a common presentation.

Patients with known Sjögren syndrome should not be taken lightly for their complaint of dry eyes or dry mouth, as these chronic problems can be very distressing and obtrusive.

Inpatient care

Give attention to artificial lubricants and humidified oxygen for intubated and/or sedated patients with Sjögren syndrome.

Outpatient care

Encourage patients with Sjögren syndrome to be active. In addition, patients should be encouraged to avoid exacerbation of dryness symptoms (eg, through smoking or exposure to low-humidity environments). All patients with Sjögren syndrome should be monitored by an ophthalmologist and dentist, in addition to their rheumatologist. Certain patients may be candidates for punctal occlusion, which is usually performed by an ophthalmologist.

Monitoring

Most patients with Sjögren syndrome can be monitored at follow-up visits every 3 months and, if the patient is stable, up to every 6 months. Patients with active problems or in whom an emerging associated illness is a concern can be seen as often as monthly.

Surgical Therapy

Occlusion of the lacrimal puncta can be corrected surgically. Electrocautery and other techniques can be used for permanent punctal occlusion.

During surgery, the anesthesiologist should administer as little anticholinergic medication as possible and use humidified oxygen to help avoid inspissation of pulmonary secretions. Good postoperative respiratory therapy should also be provided. Patients are at higher risk for corneal abrasions, so ocular lubricants should be considered.

Biopsies that may be performed in association with Sjögren syndrome include the following:

- Minor salivary gland biopsy – For diagnostic purposes

- Parotid gland biopsy – If malignancy is suggested

- Biopsy of an enlarged lymph node – To help rule out pseudolymphoma or lymphoma

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com