REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Adhesive capsulitis (AC), often referred to as Frozen Shoulder, is characterized by initially painful and later progressively restricted active and passive glenohumeral (GH) joint range of motion with spontaneous complete or nearly-complete recovery over a varied period of time.

Common names for AC include:

- Frozen Shoulder

- Painful stiff shoulder

- Periarthritis

This inflammatory condition causes fibrosis of the GH joint capsule, is accompanied by gradually progressive stiffness and significant restriction of range of motion (typically external rotation).

In clinical practice it can be very challenging to differentiate early stages of AC from other shoulder pathologies.

Epidemiology /Etiology

Glenohumeral Joint

Presently unclear for this condition.

- The patho-aetiology of frozen shoulder is, however, complex and multifactorial with both genetic and environmental factors playing an important role.

- Long held hypothesis based on arthroscopic and pathologic observations, that there is an inflammatory component within the axillary fold. This is followed by stiffness and adhesions, which results in fibrosis of the synovial lining, which is associated with the inflammation.

AC may be:

- Primary – Onset is generally idiopathic (it comes on for no attributable reason)

- Secondary – Results from a known cause, predisposing factor or surgical event. A secondary frozen shoulder can be the result of several predisposing factors. For example, post surgery, post-stroke and post-injury. Where post-injury, there may be an altered movement pattern to protect the painful structures, which will in turn change the motor control of the shoulder, reducing the range of motion, and gradually stiffens up the joint.

- Three subcategories of secondary frozen shoulder include:

- Systemic (diabetes mellitus and other metabolic conditions);

- Extrinsic factors (cardiopulmonary disease, cervical disc, CVA, humerus fractures, Parkinson’s disease)

- Intrinsic factors (rotator cuff pathologies, biceps tendinopathy, calcific tendinopathy, AC joint arthritis).

Adhesive capsulitis more prevalent

- In women, as approximately 70% of individuals who present with a frozen shoulder, are females.

- Among individuals 35-65 years old, with an occurrence rate of approximately 2-5% in the general population, In China and Japan, it’s called the 50 year old shoulder due to its prevalence at that age.

- Within the diabetic population, with an occurrence rate of 20% .

- If an individual has had AC (5-34% chance of having it in the contralateral shoulder at some point as well). Simultaneous bilateral involvement has been found to occur in approximately 14% of cases.

Risk Factors & Red Flags

- Diabetes mellitus (with a prevalence of up to 20%)

- Stroke

- Thyroid disorder

- Shoulder injury (FOOSH, direct impact, dislocation)

- Dupuytren disease

- Parkinson’s

- Complex regional pain syndrome

- Avascular necrosis (rare, but can occur)

- Tuberculosis

- Shortness of breath, severe cough, any compromises to the quality of the breath

- Metastatic disease

- Rheumatisms

- Multiple joint involvement

- Fever, chills, severe (inexplicable) pain

- History of cancer (to the individual, or family)

- Any suspicion of a systemic pathology or condition.

Specific populations and populations to consider

- Diabetics: There is a high incidence of adhesive capsulitis in diabetic patients (prevalence is as high as 10 to 22 percent of individuals with diabetes mellitus versus as 2 to 4 percent of the general population). These patients generally do not respond well to treatment, as well as non diabetic patients do.

- Hypothyroidism: Can have an influence because we can develop muscle aches and tenderness and stiffness with hypothyroidism.

- Metabolic syndrome: Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of conditions occurring together that increase the risk of, amongst other things, type two diabetes.

Pathology

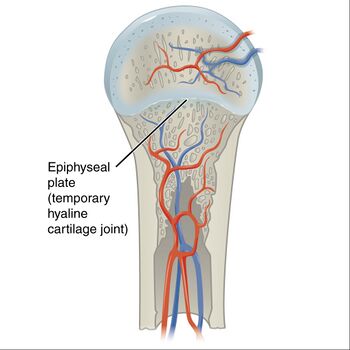

The disease process affects the antero-superior joint capsule, axillary recess, and the coracohumeral ligament.

- Patients tend to have a small joint with loss of the axillary fold, tight anterior capsule and mild or moderate synovitis but no actual adhesions.

- Contracture of the rotator cuff interval has also been seen in adhesive capsulitis patients, and greatly contributes to the decreased range of motion seen in this population.

There is continued disagreement about whether the underlying pathology is an inflammatory condition, fibrosing condition, or an algoneurodystrophic process.

- Evidence suggests there is synovial inflammation followed by capsular fibrosis, in which type I and III collagen is laid down with subsequent tissue contraction.

- Elevated levels of serum cytokines have been noted and facilitate tissue repair and remodelling during inflammatory processes.

- In primary and some secondary cases of adhesive capsulitis cytokines have shown to be involved in the cellular mechanism that leads to sustained inflammation and fibrosis.

- It is proposed that there is an imbalance between aggressive fibrosis and a loss of normal collagenous remodelling, which can lead to stiffening of the capsule and ligamentous structures.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

Patients presenting with adhesive capsulitis will often report an insidious onset with a progressive increase in pain, and a gradual decrease in active and passive range of motion.

One of the main presenting factors is loss of external rotation (ER) in a dependent position with the arm down by the side.

Patients frequently have difficulty with grooming, performing overhead activities, dressing, and particularly fastening items behind the back. Adhesive capsulitis is considered to be a self-limiting disease with sources stating symptom resolution as early as 6 months up to 11 years. Unfortunately, symptoms may never fully subside in many patients.

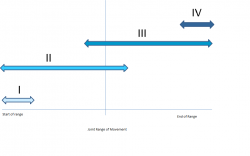

The literature reports that adhesive capsulitis progresses through three overlapping clinical phases:

- Acute/freezing/painful phase: Gradual onset of shoulder pain at rest with sharp pain at extremes of motion, and pain at night with sleep interruption which may last anywhere from 2-9 months.

- Adhesive/frozen/stiffening phase: Pain starts to subside, progressive loss of GH motion in capsular pattern. Pain is apparent only at extremes of movement. This phase may occur at around 4 months and last till about 12 months.

- Resolution/thawing phase: Spontaneous, progressive improvement in functional range of motion which can last anywhere from 5 to 24 months. Despite this, some studies suggest that it’s a self limiting condition, and may last up to three years. Though other studies have shown that up to 40% of patients may have persistent symptoms and restriction of movement beyond three years. It is estimated that 15% may have persistent pain and long term disability. Effective treatments which shorten the duration of the symptoms and disability will have a significant value on reducing the morbidity.

Disturbed Sleep

In the early part and middle part of this condition (Freezing and Frozen phase, respectfully), sleeping is often interrupted and disturbed. As the patient’s condition progresses, this can get worse and there’s good evidence that the lack of sleep, pain and depression form a tightly interconnected triangle where changes in one will affect the other two. Therefore it’s important that clinicians monitor sleep quality and use outcome measures to quantify signs and symptoms. Helpful questionnaires include the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and The Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOS-Sleep), which includes 12 items assessing sleep disturbance, sleep adequacy, somnolence, quantity of sleep, snoring, and awakening short of breath or with a headache.

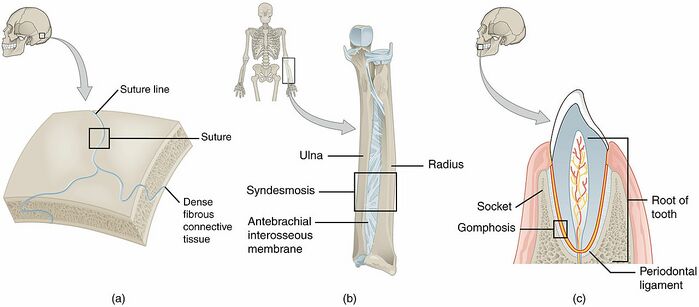

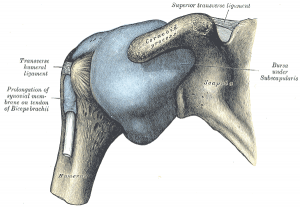

Anatomical Considerations for Adhesive Capsulitis:

There is a change in the available space and the available volume around the GH joint as the patient develops contractures through a frozen shoulder.

It is suspected that the space surrounding the GH joint reduces from between 15 to 35 cubic centimetres (cm), to 5 to 6 cubic cm. Moreover, it is suggested that capsular changes are similar to those changes which take place in the hand due to a Dupuytrens contracture. There may also be a thickening and fibrosis of the rotator interval at the top of the cuff, which then causes contractions and fibrosis of the GH ligaments. That contraction of the inferior glenohumeral ligament seems to be the one which makes the biggest difference.

When considering the anatomical location of the inferior glenohumeral ligament, it acts as the “hammock” at the bottom of the joint with an anterior posterior band. If that ligament tightens, it can reduce the amount of accessory movement which is available at the GH joint.

A quick word about the capsule: It allows an estimated 2 to 3 millimetres of distraction, which is important for the GH joint. On its own, it provides little contribution to joint stability. However, the tendons of the rotator cuff muscles insert into the capsule. Therefore, the dynamic action of the rotator cuff can have an effect on the tension within the capsule. On a whole, both ligaments and muscles insert directly into the capsule, providing an indirect link to the joint stability of the GH joint.

A final consideration is the neurovascularity, which may change locally due to the inflammatory response, which can be attributed to our understanding of a “capsulitis”.

Assessment

Subjective Assessment

Patient History

- Listen carefully to the patient’s past medical history (PMHx), this may well rule out red flags and guide the shoulder examination.

- History of presenting condition (Hx PC).

- Pain distribution and severity: Strong component of night pain, pain with rapid or unguarded movement, discomfort lying on the affected shoulder, pain easily aggravated by movement. Pain can be anywhere from the base of the skull, from down the arm into the hand.

- Aggravating activities – limited reaching, particularly during overhead (e.g., hanging clothes) or to-the-side (e.g., fasten one’s seat belt) activities. Patients also suffer from restricted shoulder rotations, resulting in difficulties in personal hygiene, clothing and brushing their hair. Another common concomitant condition with frozen shoulder is neck pain, mostly derived from overuse of cervical muscles to compensate the loss of shoulder motion

Observation of Posture and Positioning

- Scapular winging of the involved shoulder may be observed from the posterior and/or lateral views.

Screen: Upper quarter exam (UQE) and neurological screen (dermatomes, myotomes, reflexes)

- A full UQE should be performed to rule out cervical spine involvement or any neurological pathologies.

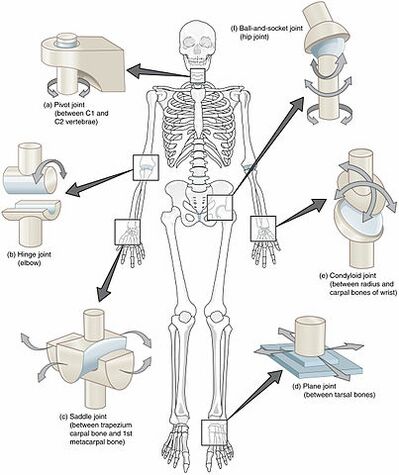

Range of Movement Assessment – Active/Passive/Overpressure

Cervical, thoracic, shoulder ROMs with OP as well as rib mobility should be performed. Reduced forward flexion, abduction, external rotation, and internal rotation range of motion are key clinical signs of adhesive capsulitis.

- Scapular substitution frequently accompanies active shoulder motion

Shoulder Flex/ABd/ER/IR

- The method of measuring ER and IR ROM in patients with suspected adhesive capsulitis varies in the literature

- Patients with adhesive capsulitis commonly present with ROM restrictions in a capsular pattern. A capsular pattern is a proportional motion restriction unique to every joint that indicates irritation of the entire joint. The shoulder joint has a capsular pattern where external rotation is more limited than abduction which is more limited than internal rotation (ER limitations > ABD limitations > IR limitations). In the case of adhesive capsulitis, ER is significantly limited when compared to IR and ABD, while ABD and IR were not seen to be different

Controversy regarding the “Capsular Pattern” of the GH Joint

When we consider the traditional teachings of Cyriax, it revolved around the capsular pattern of the GH joint. He suggested that the patient would have the greatest limitation in passive external (lateral) rotation followed by the next limitation in passive abduction, and then the last limitation in passive internal (medial) rotation.

According to Cyriax, if the patient presented in this typical capsular pattern, then they most likely had arthritis of the GH joint. If the limitations of movement didn’t follow this capsular pattern, then it was suspected to be a non-capsular pattern, suspecting a derangement or an extra articular pathology.

In the past, there has been some debate within the literature as to whether the capsular pattern of the shoulder does exist. Nonetheless, this is certainly something to consider when examining a patient.

The Importance of Evaluating the GH Ligaments

- Inferior GH ligament: The “Hammock” at the bottom of the joint. It has an anterior band, a posterior band and a less taught section in the middle (the pouch). The anterior band stabilizes the joint in ABDuction and external (lateral) rotation. As the arm moves into ABDuction and external (lateral) rotation, the anterior band will move up, across the front of the joint, providing an anterior stabilization (clinically relevant for throwing movements).

- Middle GH ligament: Stabilizes the GH joint in ADDuction plus external rotation and in ABDuction and external rotation (roughly 45 degrees of ABDuction).

- Superior GH ligament: Stabilizes the GH joint in ADDuction. Limits external (lateral) rotation and inferior translation of the humeral head.

- Coracohumeral ligament: Limits extension through it’s anterior portion. Limits flexion through the posterior portion. Also limits inferior and posterior humeral head translation.

When assessing the joint capsule, you are assessing the available freedom of movement, or accessory movement at the joint. At 60° of ABDuction, you have equal tension across all GH ligaments. This position will give an overall indication of global stiffness of the GH joint. You want to compare to the contralateral shoulder as well.

Assessment of the Superior GH ligament and the Coracohumeral ligament

Patient is supine on the treatment table, where the scapula is supported with the arm by the side. And we passively apply external (lateral) rotation until we reach the end range. Then apply an anterior glide to the humeral head, which will assess the posterior and lateral band of these two ligaments. If then you further extend the shoulder by 10 degrees, that will assess the anterior and medial band of the coracohumeral ligament.

If there is a tightening of these specific structures (GH ligaments), we can observe a change to the arthrokinematics of the shoulder joint, with increased anterior superior translation in flexion. Which will then reduce that already small subacromial space and could compromise the soft tissues transiting through the space. Moreover, there may be decreased inferior translation, decreased anterior translation at 0° and decreased posterior translation in flexion. Which in turn can lead to compromising the subacromial space and the self fulfilling prophecy of causing pain and dysfunction.

Assessment of the Middle GH ligament

Again, patient lying in supine on the treatment bed, so their scapular is stabilized with the arm by the side. You then take the glenohumeral joint into 10° extension. Apply external (lateral) rotation to the end of range. At that point, move the shoulder into 45° of ABDuction and then apply an antero-medial glide in the plane of the scapula. You are basically placing a sort of posterior anterior pressure, again in the plane of the scapula. Evaluate the degree of translation and compare that to the contralateral side.

Assessment of the Inferior GH Ligament

The Anterior Band: Patient lying supine on the treatment table with the scapular supported. Have them in the same position as they were before for the evaluation of the other GH ligaments. Move the shoulder from that 45° position with extension, towards 90° of ABDuction with external rotation. Then apply an anterior-medial glide, so to apply pressure to the head of the humerus. Evaluate the quality and quantity of the humeral head translation. Practice caution in this position if you suspect any sort of instability. This is similar to the Apprehension Test. Be cautious of a subluxation or a dislocation.

The Posterior Band: Patient lying supine on the treatment table with the scapular supported. Bring the shoulder into ABDuction and internal (medial) rotation. Similarly, this band moves up across the middle of the back of the joint to give it that posterior stability. Their shoulder is in 90° abduction and 10° of extension. Apply full internal (medial) rotation. Apply a gentle anterior-lateral glide to the GH joint. Apply pressure and evaluate the quality and quantity of the accessory movements.

Assessment of the Posterior Capsule: Patient lying supine on the treatment table with the scapular supported. Place the shoulder in 90 degrees of flexion, full internal (medial) rotation, and then end range of horizontal ADDuction. Apply an axial stress in a posterior lateral direction. You are going across the plane of the scapula and you are looking for that translation. This is similar to testing for posterior instability of the GH joint (that test is for a posterior labral tear). We aware of the response from the patient in this position.

Resisted Muscle Tests

Shoulder external rotation (ER)/ Internal rotation (IR)/abduction (ABd) (seated) should be performed.

- Patients with adhesive capsulitis present with weakness in shoulder ER, IR and ABd relative to the asymptomatic side.

- Patients may also present with significant muscle guarding. Be aware of the stage of Adhesive Capsulitis you suspect your patient to be in, before subjecting them to muscle testing (manual muscle testing or with an isokinetic dynamometer).

Joint Accessory Movements

Glenohumeral joint:

- Anterior

- Inferior

- Posterior

- Posterior capsule stretch

A reminder of the arthrokinematics of the shoulder joint. A review of coupled movements:

- Flexion / internal (medial) rotation / horizontal flexion = anterior superior translation of the humeral head.

- Extension and external (lateral) rotation / abduction and external (lateral) rotation = posterior translation of the humeral head.

In patients with adhesive capsulitis, the anterior and inferior capsule will be the most limited but joint mobility will be restricted in all directions.

Why accessory movements with Adhesive Capsulitis?

Evaluating accessory movements will provide the clinician with an indication of the global stiffness of the shoulder joint. When assessing a shoulder, it is important to always compare any movements (including accessory glides) to the contralateral shoulder. Keep in mind that the assumption is that contralateral shoulder is “normal”. As previously outlined, this is not always the case with a frozen shoulder. The quality of the movement / accessory movements is just as important as the quantity.

Understanding the capsule – Proprioceptive Role

If the capsule is tight, then the glenohumeral translations (accessory movements) will occur earlier in range of motion and most likely to greater excess. Also, the capsule is not simply a passive structure which holds everything “together” with a couple of identified thickenings (ligaments). It is also a major proprioceptive end organ.

If the capsule becomes tight, it will have an effect on the proprioception system as this will stimulate the localized mechanoreceptors and increase the feed forward mechanism within the joint; which could in turn increase capsular tightness. This could cause a continuous loop of tightening the capsule, stimulating the mechanoreceptors, increasing the local stabilizing muscles (such as the rotator cuff), which will ultimately increase the tension around the joint. It is highly suspected the adhesive capsulitis has a strong neurological component.

Special Tests

Shoulder Shrug Sign (inability to lift the arm to 90° abduction without elevating the whole scapula or shoulder girdle) Previously was associated with rotator cuff disease, but more commonly was associated with glenohumeral arthritis, adhesive capsulitis, and massive cuff tears.

Yang et al. investigated the reliability of 3 function related tests in patients with shoulder pathologies via a non-experimental study

Hand to neck (Figure 1A)

- Shoulder flexion + abduction + ER

- Similar to ADLs such as combing hair, putting on a necklace

Hand to scapula (Figure 1B)

- Shoulder extension + adduction + IR

- Similar to ADLs such fitting a bra, putting on a jacket, getting into back pocket

Hand to opposite scapula (Figure 1C)

- Shoulder flexion + horizontal ADDuction (The Scarf Test – cross body adduction).

These tests require appropriate elbow, scapulothoracic, and thoracic mobility and these areas should be cleared of pathology first. If a patient is unable to complete the motion, other structures outside of the shoulder joint may be the limiting factor.

Reliability of the three tests was excellent and correlation between them was moderate.

These functional measures appear to be helpful for their objectivity in measuring shoulder dysfunction. However, even though the tests mimic fundamental ADL movements, the direct relationship between these tests and activities of daily living cannot be assumed.

Other

No specific clinical test for adhesive capsulitis has been reported in the literature and there remains no gold standard to diagnose adhesive capsulitis. While there are no confirmed diagnostic criteria, a recent study determined a set of clinical identifiers that achieved a general consensus amongst experts for the early stages of primary (idiopathic) adhesive capsulitis. The following tools can be used to help determine the stage of adhesive capsulitis and/or its irritability status.

Consensus was achieved on eight clinical identifiers collated into two discrete domains (pain and movement) as well as an age component.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Movement

- Global loss of active and passive ROM

- Pain at end-range in all directions

Onset

- > 35 years of age

Physical Therapy Management

The definitive treatment for adhesive capsulitis remains unclear even though multiple interventions have been studied. For most patients, enrolling in a physical therapy program is the key to recovery. Also, a meta-analysis carried out by Tedla & Sangadala in 2019 concluded that PNF is very effective in decreasing pain, increasing ROM, improving function, and reducing disability.

Importance of Patient Education

For the treatment of adhesive capsulitis, patient education is essential in helping to reduce frustration and encourage compliance. It is important to emphasize that although full range of motion may never be recovered, the condition will spontaneously resolve and stiffness will greatly reduce with time. It is also helpful to give quality instructions to the patient and create an appropriate home exercise program (HEP) that is easy to comply with as daily exercise is critical in relieving symptoms. The below video gives a good outline of a HEP for the 3 phases of AC.

Techniques

Initial Phase: Painful, Freezing

Pain relief and the exclusion of other potential causes of your frozen shoulder is the focus during this phase.

Very gentle shoulder mobilisation, muscle releases, acupuncture, dry needling and kinesiology taping for pain-relief can assist during this painful inflammation phase. The application of a TENS machine was shown reduce pain and increase range of motion.

Modalities, such as hot packs, can be applied before or during treatment. Moist heat used in conjunction with stretching can help to improve muscle extensibility and range of motion by reducing muscle viscosity and neuromuscular mediated relaxation. In a randomised study by Bal et al., patients improved with combined therapy which involved hot and cold packs applied before and after shoulder exercises were performed.[6] However, Jewell et al, claimed that ultrasound, massage, iontophoresis and phonophoresis reduced the chances of positive outcomes. Green et al. suggested that there is no evidence of the effect of ultrasound in shoulder pain (mixed diagnosis), adhesive capsulitis or rotator cuff tendinitis.

As alluded to, treatment should be customised to each individual based on the stage of the condition.

Pain relief should be the focus of the initial phase, also known as the painful, freezing Phase. During this time, any activities that cause pain should be avoided. Better results have been found in patients who performed simple pain free exercise, rather than intensive physical therapy In patients with high irritability, range of motion exercises of low intensity and short duration can alter joint receptor input, reduce pain, and decrease muscle guarding. Stretches may be held from one to five seconds in a pain free range, 2 to 3 times a day. A pulley may be used to assist range of motion and stretch, depending on the patient’s ability to tolerate the exercise. Core exercises include pendulum exercise, passive supine forward elevation, passive external rotation with the arm in approximately 40 degrees of abduction in the plane of the scapula, and active assisted range of motion in extension, horizontal adduction, and internal rotation.

Although performed on a single patient only, Ruiz et al performed positional stretching of the coracohumeral ligament in the initial phase of adhesive capsulitis. The patient’s Disabilities of Arm Shoulder and Hand (DASH) scores improved from 65 to 36 and Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) scores improved from 72 to 8 and passive external rotation increased from 20 to 71 degrees. The stretches performed focused on providing positional low load and prolonged stretch to the CHL and the area of the rotator interval capsule following anatomical fibre orientation. The rationale behind this was to produce tissue remodelling through gentle and prolonged tensile stress on the restricting tissues. While a cause and effect relationship cannot be inferred from a single case, this report may help with further investigation regarding therapeutic strategies to improve function and reduce loss of range of motion in the shoulder and the role that the CHL plays in this.

In the case of adhesive capsulitis, physical therapy can also be a complement to other therapies (such as steroid injections as discussed previously), especially to improve the range of motion of the shoulder. Bal et al suggested that concomitant exercises to steroid injections should include isometric strengthening in all ranges once motion returned to 90% of normal ranges, theraband exercises in all planes, scapular stabilisation exercises, and later, advanced muscular strengthening with dumbbells.)

Second Phase: Decreased Range of Movement

Gentle and specific shoulder joint mobilisation and stretches, muscle release techniques, acupuncture, dry needling and exercises to regain your range and strength are used for a prompt return to function. Care must be taken not to introduce any exercises that are too aggressive. In particular, mobilisation with movement (MWM) style techniques appears the most effective and more effective than stretching exercises alone.MWM’s are specific-techniques performed by suitably-trained shoulder physiotherapists.

A prospective study by Griggs et al, demonstrated success of a non-operative treatment through a four-direction shoulder stretching exercise programme in which 90% of the patients reported a satisfactory outcome. During the second phase of treatment, movement with mobilisation and end range mobilisations are recommended.Mobilisation with movement can also correct scapulohumeral rhythm significantly better than end range mobilisation. The goal for end range mobilisation is not only to restore joint range, but also to stretch contracted peri-articular structures, whereas mobilisation with movement aims to restore pain free motion to the joints that had antalgic limitation of range of motion.

Gaspar and Willis. demonstrated that physical therapy paired with dynamic splinting had better outcomes compared to physical therapy alone or dynamic splinting alone. The patients in this group of combined treatments received physical therapy twice a week and a Shoulder Dynasplint System (SDS) for daily end range stretching. The combination of physical therapy with dynamic splinting had significant improvements in active, external rotation in patients with adhesive capsulitis.

Third Phase: Resolution

Provide you with exercise progressions including strengthening exercises to control and maintain increased range of movement.

Physiotherapy is most effective during this thawing phase.Progressed primarily by increasing stretch frequency and duration, whilst maintaining the same intensity, as tolerated by the patient. The stretch can be held for longer periods and the sessions per day can be increased. As the patient’s irritability level reduces, more intense stretching and exercises using a device, such as a pulley, can be performed to influence tissue remodelling.

Rational for Specific Techniques

Mechanical changes that occur as a result of mobilisations may include the break- up of adhesions, realignment of collagen, or increased fibre glide when specific movements stress certain parts of the capsular tissue. These techniques are intended to increase joint mobility by inducing changes in synovial fluid formation. High grade mobilisation techniques (HGMT) have been shown to be helpful for improving range of motion in patients with adhesive capsulitis for at least three months. In a study by Vermeulen et al., patients were given inferior, posterior, and anterior glides as well as a distraction to the humeral head. These techniques were performed at greater elevation and abduction angles if glenohumeral joint range of motion increased during treatment. Patients who received HGMT received these mobilisations at Maitland Grades III and IV according to the subjects’ tolerance with the intention of treating the stiffness. Patients were allowed to report a dull ache as long as it did not alter the execution of the mobilisations or persist for more than four hours after treatment. However, patients who received low-grade mobilisation techniques (LGMT) at Mailtand Grades I or II reported no pain. Statistically significant greater change scores were found in the HGMT group for passive abduction (at 3 and 12 months) and for active and passive external rotation (at 12 months) when compared with the low-grade mobilisation techniques. High grade mobilisation techniques appear to be more effective for increasing joint mobility and reducing disability. Further studies are needed, however, to investigate whether HGMTs applied during earlier stages of adhesive capsulitis are as effective.

Johnson et al. reported that joint mobilisations, in particular posterior glenohumeral glides, can help decrease deficits in external rotation, more so than anterior glenohumeral glides. Both techniques had a significant decrease in pain, but there was greater improvement in external rotation range of motion with the posterior mobilisation treatment. End range mobilisation is also more effective than mid-range mobilisation in increasing motion and functional mobility. Overall, there are significant beneficial effects of joint mobilisation and exercise for patients with adhesive capsulitis.

Rationale for Stretching

Research regarding connective tissue stretch duration and intensity has produced 3 findings. Firstly, that high intensity, short duration stretching aids the elastic response, whilst low intensity, prolonged duration stretching aids the plastic response. Secondly, a direct correlation exists between the resulting proportion of plastic, permanent elongation and the duration of a stretch. Lastly, a direct correlation exists between the degree of either trauma or weakening of the stretched tissues and the intensity of a stretch. McClure et al, stated that the maximum TERT (Total End Range Time) or the total amount of time the joint is held at near end range position, will be different for each person and is often affected by personal circumstances such as their job or other responsibilities that may prevent a patient from increasing TERT.

Progressions

Manual techniques and exercise should only be progressed as the patient’s irritability reduces. Patient response to treatment should be based on their pain relief, improved satisfaction, and functional gains, rather than restoration of range of motion. Usually, patients are discharged when significant pain reduction is reached, a plateau of motion gains are noticed for a period of time, and after improved functional motion and satisfaction have reached their peak. Progression for stretching via dynamic splinting is based on patient tolerance, as well. Gaspar and Willis, suggested that if patients experience discomfort or stiffness lasting more than an hour after the splint is removed, the duration of treatment is reduced for the next two stretching sessions. Only after stretching for a total of 60 minutes (30 minutes twice a day) is tolerated, is it suggested that the tension is then increased, every two weeks based on tolerance, without discomfort lasting more than one hour following every stretching session.

Despite extensive research, further prospective randomized studies comparing different treatments are needed to formulate precise guidelines about diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic adhesive capsulitis. The lack of validity, poor standardization of terminology, methodology, and outcome measures in the investigations undermines clinical application. Therefore, more rigorous investigations are needed to compare the cost and effectiveness of physical therapy interventions.

Exercise examples:

Figure 1: Active assisted end range movements in flexion, external rotation and extension. Figure 2: Active assisted end-range movements in internal rotation, horizontal adduction and flexion.

Figure 3: Coracohumeral Ligament Stretch

Figure 4: Active assisted movements in elevation and external rotation with a cane.

Figure 5: Posterior mobilizations of the humeral head in supine.

Figure 6: Anterior mobilizations of the humeral head in supine.

The definitive treatment for adhesive capsulitis remains unclear even though multiple interventions have been studied. Previously published prospective studies of effective treatment have demonstrated conflicting results for improving shoulder range of motion in patients with this condition. Non-operative interventions include patient education, modalities, stretching exercises, and joint mobilizations. Levine et al. reported that 89.5% of ninety eight patients with frozen shoulder responded well to non-operative management. Reviewed studies suggest that many patients have benefited from physical therapy and showed reduced symptoms, increased mobility, and/or functional improvement. A Cochrane Review by Green et al, however, states that there is no evidence that physiotherapy alone is of benefit for adhesive capsulitis.

Rational for Motor Control Exercises

There is emerging scientific support that “muscle guarding” and pathological motor control of the shoulder may play a significant role in the restrictive movements of the shoulder; rather than solely a contracted capsule. Therefore, motor control and exercise therapy is indicated in a clinical setting.

Goals:

- Restoration of normalized recruitment pattern.

- Balanced recruitment of agonists / antagonists / synergistic muscles of the shoulder (in terms of strength, timing, and coordination).

- Appropriate level of muscle recruitment for low and high loads for the shoulder (a pathological shoulder tends to use high levels of muscle recruitment for low loads).

- Restore motor control during isometric, concentric and eccentric muscle activity.

Additional considerations for clinical practice

Because Adhesive Capsulitis is painful, chronic and generally stressful for a person, relaxation techniques are important to consider and integrate into a treatment plan. Some strategies include:

- Desensitization techniques

- Breathing exercises

- Cognitive behavioural therapy

- Distracting the patient during more “aggravating” treatments or exercises.

The importance of considering the shoulder complex as a member of a kinetic chain

It is estimated that during shoulder movement, 50% of forces produced in the shoulder girdle come from the waist down (lower extremities), 30% comes from around the trunk (core stabilization) and 20% comes from local efforts (upper extremities and the shoulder complex). If we can start to incorporate the kinetic chain as a whole during rehabilitation, this will allow for much more efficient movements around the shoulder joint. What is required is mobility and stability throughout the kinetic chain, in order to optimize the function of the shoulder.

Conservative Rehabilitation – What works?

What do we do? With respect to manual therapy, there is an interesting Cochrane review by Page et al. 2014 which shows that the combination of manual therapy and exercise may not be as effective as a steroid injection in the short-term. However, the results are generally inconclusive.

Vermeulen et al. (2006) showed that it is possible to increase range and decrease pain with high grade mobilizations (Grade III & IV) of the GH joint. Contrastingly, Page et al. suggested that there was limited evidence or benefit of manual therapy and exercise when used in isolation to treat Adhesive Capsulitis. The strongest support at the moment suggests that conservative treatments (manual therapy and exercise) should be used in adjunct with a corticosteroid injection.

Differential Diagnosis

Some conditions can present with similar impairments and should be included in the differential diagnosis. These include, but are not limited to, osteoarthritis, acute calcific bursitis/tendinitis, rotator cuff pathologies, parsonage-Turner syndrome, a locked posterior dislocation, or a proximal humeral fracture.

- Shoulder Osteoarthritis (OA). Both may have limited abduction and external rotation AROM but with OA, PROM will not be limited. OA will also present with the most limitations with flexion whereas this is the least affected motion with adhesive capsulitis. Radiography can be used to rule out pathology of osseous structures.

- Acromioclavicular joint dysfunction: Likely to occur with a high arch of pain, pain with a cross-body adduction (Scarf Test), and palpation of the acromioclavicular joint itself.

- Bursitis. Bursitis presents very similarly to adhesive capsulitis, especially compared to the early phases. Patients with bursitis will present with a non-traumatic onset of severe pain with most motions being painful. A main difference will be the amount of PROM achieved. Adhesive capsulitis will be extremely limited and painful whilst patients with bursitis, although painful, will have a larger PROM.

- Parsonage-Turner Syndrome (PTS). PTS occurs due to inflammation of the brachial plexus. Patients will present without a history of trauma and with painful restrictions of all motions. The pain with PTS usually subsides much quicker than with adhesive capsulitis and patients eventually display neurological problems (atrophy of muscles or weakness) that are seen several weeks after the initial onset of pain.

- Rotator Cuff (RC) Pathologies. The primary way to distinguish RC pathologies from adhesive capsulitis is to examine the specific ROM restrictions. Adhesive capsulitis presents with restrictions in the capsular pattern while RC involvement typically does not. RC tendinopathy may present similarly to the first stage of adhesive capsulitis because there is limited loss of external rotation and strength tests may be normal. MRI and ultrasonography can be used to identify soft tissue abnormalities of the soft tissue and labrum.

- Posterior Dislocation. A posteriorly dislocated shoulder can present with shoulder pain and limited ROM, but, unlike adhesive capsulitis, it is related to a specific traumatic event. If the patient is unable to fully supinate the arm while flexing the shoulder, the clinician should suspect a posterior dislocation.

- “Active Muscle Guarding” (Motor Control Dysfunction) Hollmann et al. (2015) reported in their study that all of the patients suspected to have Frozen Shoulder showed a significant increase in range of motion under anesthesia, which confirms that some cases might have been falsely diagnosed with Frozen Shoulder and that the loss of range of motion cannot only explained by capsular contractions.

Outcome Measures

Currently the diagnosis of primary adhesive capsulitis is based on the findings of the patient history and physical examination.

The following outcome measures have been used in studies researching adhesive capsulitis.

- Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI)

- Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand scale (DASH)

- American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Standardized Shoulder Assessment Form (ASES)

- Simple Shoulder Test (SST)

- Penn Shoulder Scale (PSS)

- NPRS

- VAS

- SF-36

Roy et al examined the psychometric properties of the SPADI, DASH, ASES and SST were examined. Reliability, construct validity and responsiveness were all found to be favourable for various shoulder pathologies, but the review did not address their strength relative to adhesive capsulitis, specifically.

Medical Management

Although Adhesive Capsulitis is a self-limiting condition, it can take up to two to three years for symptoms to resolve and some patients may never fully regain full motion.Treatment for pain, loss of motion, and limited function rather than take the wait-and-see approach is therefore important. Various interventions have been researched that address the treatment of the synovitis and inflammation and modify the capsular contractions such as oral medications, corticosteroid injections, distension, manipulation, and surgery. Even though many of these treatments have shown significant benefits over no intervention at all, definitive management regimens remain unclear. It is suggested that the primary treatment for adhesive capsulitis should be based around physical therapy and anti-inflammatory measures, these outcomes, however, are not always superior to other interventions.

Corticosteroid Injections

Corticosteroid injections are often used to manage inflammation as it is understood that inflammation is a key factor in the early stages of the condition. The injections aim to reduce the painful synovitis occurring within the shoulder. This can limit the development of fibrosis and adhesions within the capsule, potentially shortening the natural history of the disease. Hence they are thought to be more useful in the early, painful and freezing stage of the condition due to the involvement of inflammation, rather than in the latter stages when fibrous contractures are more apparent.

An important to note to consider is that often when we inject a steroid, there is a local anaesthetic that will reduce the pain and that could aid with improving the motor control of the shoulder complex.

Many studies have been performed and reviewed comparing corticosteroid injections to physical therapy, but results have been contradictory. It has been concluded that corticosteroid injections provide significantly greater short term benefits (4-6 weeks), especially in pain relief, but there is little to no difference in outcomes by 12 weeks compared to physical therapy. The majority of studies, however, investigating corticosteroid injection as a treatment option do not define what stage the patients are in and had variations in the volumes of corticosteroid used. It has been shown that the benefits may not only be dose dependent, but also dependent on the duration of symptoms as well. Therefore, the earlier the injection is received, the quicker the individual will recover. Contraindications to corticosteroids use include a history of infection, coagulopathy, or uncontrolled diabetes.

Ultimately, corticosteroid injections have been shown to have success rates ranging from 44-80% with rapid pain relief and improved function occurring mainly in the first weeks of treatment. It is a first line treatment for patients with pain as their predominant complaint in the early stages of adhesive capsulitis. Though intra-articular steroid injection may be beneficial early on, its effect may be small and not well maintained and should be offered in conjunction with physical therapy.

Location of the injections:

i) Sub-acromial injection

ii) Intra-articular injection

A recent study by Cho et al. found that a combination of both injections had an additive effect on increasing range of motion around the shoulder.

Recommendations:

- Injection for relieving shoulder disability and pain. Physical therapy for improving motion in the painful freezing stage

- If patients fail to progress within 3-6 weeks with physical therapy alone or patient’s symptoms worsen, they should be offered the option of a corticosteroid injection.

Manipulation Under Anesthesia (MUA)

An extensive post-manipulation programme begins immediately after release of the capsule. They are often prescribed active assisted range of motion exercises that should be performed every two hours during waking hours, for the next 24 hours. Patients are also instructed to ice their shoulder for 20 minutes every two hours with their hand resting behind their head. Post manipulation programs are designed to maintain gains in shoulder mobility and should specifically address each individual’s impairments.

Translation Mobilisation under Anesthesia

An alternative to traditional MUA is translation mobilization under anesthesia, which has been identified in an attempt to avoid the complications associated with the traditional approach. This procedure involves the use of gliding techniques with static end range capsular stress with a short amplitude high velocity thrust, if needed, as opposed to the angular stretching forces in manipulation under anesthesia.2 to 3 30 second sets of low velocity, oscillatory mobilizations (Maitland Grade IV-IV+) are performed initially in the same directions as traditional manipulation under anesthesia (anteriorly, posteriorly, and inferiorly). If an immediate increase in passive range of motion is not seen, a high velocity, low amplitude manipulation may be performed. This technique appears to be a safe and efficacious alternative for treatment of patients resistant to conservative treatment, however, higher level studies are needed for verification.

- If a patient has persistent symptoms, particularly in decreased shoulder motion, after at least 6 months of conservative treatment, manipulation under anesthesia is an effective technique to improve mobility, pain and disability.

- Contraindications and complications do exist and should be relayed to the patient.

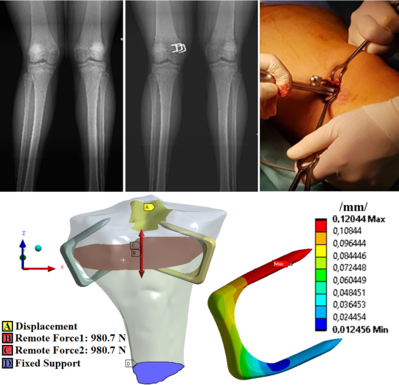

Arthroscopic Capsular Release (Arthroscopic arthrolysis)

Arthroscopic capsular release is the preferred method over open release in patients with painful, disabling adhesive capsulitis that is unresponsive to at least 6 months of non-operative treatment.

The purpose of this surgical intervention is a capsular release, where they cut and remove the thickened, swollen, inflamed capsule as well as to help restore normal movement of the joint.

It has been found to be a reliable and effective method for restoring range of motion and is especially recommended for diabetics and in post-operative or post-fracture adhesive capsulitis patients. It has become the most popular method of treating non-responsive adhesive capsulitis despite the lack of higher level trials comparing it to MUA. This is because it allows a more controlled and selective release of the contracted capsule compared to manipulation which ruptures the capsuloligamentous structures and avoids the complications associated with MUA. Debate exists over which structures should be arthroscopically released with the rotator cuff and coracohumeral ligament being the most common structures released.

Recommendations:

- If patient is unresponsive to at least 6 months of conservative treatment, arthroscopic capsular release alone or in conjunction with manipulation, has been shown to be effective in restoring range of motion.

- Avoids complications associated with manipulation under anesthesia and is recommended in diabetics and post-operative or post-fracture adhesive capsulitis patients.

Post Surgical Considerations

Post surgery, whatever surgical technique was employed, clinicians need to consider the integrity of the local nerves. They could be disturbed by the arthroscopy as well, because there are many local nerves surrounding the shoulder joint (in close proximity to where the arthroscopy portals are located).

Also, the shoulder will not have been overly mobile for months (possibly years). Following surgery, there could be a sudden restoration of movement, which could in turn irritate the nerves.

The main nerves of concern are:

- Radial

- Ulnar

- Median

- Axillary

- Suprascapular

- Musculocutaneous

- Long thoracic

- Also possibly the brachial plexus as a whole

- The evaluation of the cervical spine and nerve root mobility should also be a priority post-surgery.

Other Treatments

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have traditionally been given to patients with adhesive capsulitis, but there is no high level evidence that confirms their effectiveness.[1][35]

Oral steroids have also been utilized in these patients and result in some improvement in function, but their effects have not shown long term benefits and combined with their known adverse side effects, should not be regarded as a routine treatment.[1][35][38] Another technique that shows some short term benefit with rapid relief of symptoms is distension arthrography. This technique involves the injection of a solution (saline alone or combined with corticosteroids) causing rupture of the capsule by hydrostatic pressure. It is still undetermined whether joint distension with saline solution combined with corticosteroids provides more benefit than distension with saline alone or corticosteroid injection alone. There is a lack of reliable evidence when determining the effectiveness of this technique and further research needs to be performed to verify any clinical benefit.

Suprascapular nerve blocks are thought to temporarily disrupt pain signals to allow normalization of the pathological, neurological processes perpetuating pain and disability. There is some evidence of benefit with suprascapular nerve blocks, though the exact mechanism behind this benefit remains unclear and higher level evidence is needed to establish this as a treatment for adhesive capsulitis.

Hydrodilatation (distension arthrography) has emerged as a potential non-surgical option in the management of frozen shoulder. Although therapeutic regimens will differ between units, common to most is the instillation of a large volume of saline containing steroid, local anaesthetic and contrast material (dye) into the GH joint under imaging guidance (30 ml). The goal is capsular expansion.

The stated benefits of the procedure are achieved through hydraulic distension of the capsule (sometimes referred to as “pops” in the capsule) and the main purpose of initial work was to achieve capsular rupture. However, there is little in the way of evidence to determine whether capsule rupture must be achieved in order for the procedure to be successful, or whether it is the capsular distension which is most important. Most studies comment on their intention to achieve capsular rupture but have not investigated this.

A Cochrane review in 2008 demonstrated only silver-level evidence to support hydrodilatation as a treatment modality to improve short-term pain and function, up to three months.

Clinical Bottom Line

According to a Cochrane review by Green et al, there is little evidence to support or refute the use of any of the common interventions listed for Adhesive Capsulitis. There are also no studies with objective data supporting the timing of when to switch to invasive treatments such as manipulation under anesthesia or arthroscopic release, which are not usually performed until 6 months of conservative treatment have been unsuccessful. Unfortunately this exposes more than 40% of patients with Adhesive Capsulitis to a long period of disability and pain.

Treatments should be tailored to the stage of the disease because the condition has a predictable progression. Moreover, we need to consider the causative factors (the primary and the secondary factors) of the disease for the individual.

We also need to be upfront with our patients with regards to the nature of the disease as well as factors which may not be directly addressed with physiotherapy (for example, if the patient is diabetic, it will potentially be a longer recovery and require the intervention of a multi-disciplinary team). Managing expectations with your patient is key to a successful recovery.

We, as clinicians, need to consider an appropriate intervention at the right stage. We need to manage the pain levels as soon as possible. It’s very important, and again, if we can do things that can help them sleep, that can have a massive benefit on their pain levels, but also their emotional state.

During the painful freezing stage, treatment should be directed at pain relief with pain guiding activity. NSAIDs, physical therapy and steroid injection are all suggested interventions during this stage of adhesive capsulitis. Once the patient is in the adhesive stage, injections are no longer indicated because the inflammatory stage of the disease has passed. The focus should instead switch to more aggressive stretching and MUA or surgical release if symptoms are unresponsive to conservative treatment and quality of life is compromised.

There is no definitive treatment for adhesive capsulitis. However, the literature suggests interventions should be tailored to the stage of the disease based on its progressive nature. During the initial/painful freezing stage, treatment should be directed at pain relief with pain guiding activity. NSAIDs and steroid injection, stretching, strengthening and range of motion exercises, as well as Maitland Grade I-II mobilizations have been suggested to improve function and reduce pain and disability. As the patient progresses to the adhesive stage, intervention should focus on aggressive, end-range stretches combined with Maitland Grade III-IV mobilizations. At six months, if functional disability persists despite conservative treatment, mobilizations under anaesthesia (MUA) or arthroscopic capsular release may be indicated.

The bottom line remains individualizing the treatment plan to the patient as well as focusing on the quality of the movement, not overly obsess with the quantity of the movement.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com