REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Reactive arthritis is joint pain and swelling triggered by an infection in another part of the body — most often the intestines, genitals or urinary tract.

This condition usually targets the knees, ankles and feet. Inflammation also can affect the eyes, skin and the tube that carries urine out of the body (urethra). Previously, reactive arthritis was sometimes called Reiter’s syndrome.

Reactive arthritis isn’t common. For most people, signs and symptoms come and go, eventually disappearing within 12 months.

for consultant or book an online appointment- gmail- sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Causes

Reactive arthritis develops in reaction to an infection in your body, often in your intestines, genitals or urinary tract. You might not be aware of the triggering infection if it causes mild symptoms or none at all.

Numerous bacteria can cause reactive arthritis. Some are transmitted sexually, and others are foodborne. The most common ones include:

- Campylobacter

- Chlamydia

- Clostridioides difficile

- Escherichia coli

- Salmonella

- Shigella

- Yersinia

Reactive arthritis isn’t contagious. However, the bacteria that cause it can be transmitted sexually or in contaminated food. Only a few of the people who are exposed to these bacteria develop reactive arthritis.

Pathophysiology

ReA is usually triggered by a GU or GI infection (see Etiology). Evidence indicates that a preceding Chlamydia respiratory infection may also trigger ReA. The frequency of ReA after enteric infection averages 1-4% but varies greatly, even among outbreaks of the same organism. Although severely symptomatic GI infections are associated with an increased risk of ReA, asymptomatic venereal infections more frequently cause this disease. About 10% of patients have no preceding symptomatic infection.

ReA is associated with histocompatibility leukocyte antigen B-27 (HLA-B27), a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecule involved in T-cell antigen presentation. Results for HLA-B27 are positive in 65-96% of patients (average, 75%) with ReA. Patients with HLA-B27, as well as those with a strong family clustering of the disease, tend to develop more severe and long-term disease.

Sun et al reported that susceptibility to ReA arthritis is affected by the levels of certain killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs), which correspond with specific HLA-C ligand genotypes. In individuals with high levels of activating and low levels of inhibitory KIR signals, pathogens can more easily trigger natural killer cell and T cell innate and adaptive immune responses, resulting in the overproduction of cytokines that contribute to the pathogenesis of ReA.

Their study of 138 patients with ReA found that KIR2DS1, which is activating, is associated with susceptibility to ReA, when present alone or in combination with the HLA-C1C1 genotype. KIR2DL2, which is inhibitory, in combination with the HLA-C1 ligand is associated with protection against ReA. Patients with ReA had significantly lower frequencies of KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL5 than did controls. The presence of more than seven inhibitory KIR genes was protective.

The mechanism by which the interaction of the inciting organism with the host leads to the development of ReA is not known. It is possible that microbial antigens cross-react with self-proteins, stimulating and perpetuating an autoimmune response mediated by type 2 T helper (Th2) cells. Chronicity and joint damage have been associated with a Th2 cytokine profile that leads to decreased bacterial clearance.

Synovial fluid cultures are negative for enteric organisms or Chlamydia species. However, a systemic and intrasynovial immune response to the organisms has been found with intra-articular antibody and bacterial reactive T cells. Furthermore, bacterial antigen has been found in the joints. Thus, the elements for an immune-mediated synovitis are present.

Synovitis in ReA is mediated by proinflammatory cytokines. Native T cells under the influence of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and other cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-6, differentiate into Th17 effector cells, which then produce IL-17. IL-17 is one of the major cytokines elevated in the synovial fluid of these patients. Deficiencies in regulatory mechanisms can result in increased proinflammatory cytokine production and worse outcome.

The Toll-like receptors (TLRs) recognize different extracellular antigens as part of the innate immune system. TLR-4 recognizes gram-negative lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Studies in mice and humans showed abnormalities in antigen presentation due to downregulation of TLR-4 costimulatory receptors in patients with ReA. Subsequent studies implicated TLR-2 polymorphism associated with acute ReA; however, its role is still disputed.

Molecular evidence of bacterial DNA (obtained via polymerase chain reaction [PCR] assay) in synovial fluids has been found only in Chlamydia -related ReA, and a single placebo-controlled trial of a tetracycline derivative (ie, lymecycline) has shown a reduction in the duration of acute Chlamydia -related, but not enteric-related, ReA. This suggests that persistent infection may play a role, at least in some cases of chlamydial-associated ReA.

In a subsequent trial, the combination of doxycycline and rifampin was superior to doxycycline alone in reducing morning stiffness and swollen and tender joints in patients with undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy.

The role of HLA-B27 in this scenario remains to be fully defined. The following theories have been proposed:

- Molecular mimicry – This hypothesis suggests that a similarity exists at the molecular level between the HLA-B27 molecule and the inciting organisms, allowing the triggering of an immune response and the subsequent development of clinical disease

- HLA-B27 as a receptor for certain bacteria – At present, there is little evidence either to confirm or to refute this hypothesis

- Defective class I antigen-mediated cellular response – This hypothesis suggests that the HLA-B27 molecule may be a defective molecule associated with an aberrant cytotoxic T-cell response

ReA can occur in patients with HIV infection or AIDS—most likely because both conditions can be sexually acquired, rather than because ReA is triggered by HIV. The course of ReA in these patients tends to be severe, with a generalized rash resembling psoriasis, profound arthritis, and frank AIDS. HLA-B27 frequency is the same as that associated with non–AIDS-related ReA in a similar demographic group. This association points out the likely importance of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells as compared with CD4+ Th cells in the pathogenesis of ReA.

ReA is sometimes divided into epidemic and endemic forms. Whereas a triggering agent can be identified for epidemic ReA, none has been identified for endemic ReA. Differentiation between the 2 types of ReA may be difficult in some cases; however, it is not essential to either diagnosis or treatment.

for consultant or book an online appointment- gmail- sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

epidemiology

International statistics

The infections that incite ReA may vary with geographic location. For example, Y enterocolitica is more commonly identified in Europe than in North America and thus is responsible for more cases of ReA in countries such as Finland and Norway. The occurrence of ReA appears to be related to the prevalence of HLA-B27 in a population and to the rate of urethritis/cervicitis and infectious diarrhea.

More than 40 subtypes of HLA-B27 are known; those associated with the spondyloarthropathies are HLA-B2702, B2704, and B2705. These subtypes may be somewhat geographically segregated. For example, the subtype B2705 is found predominantly in Latin America, Brazil, Taiwan, and parts of India. It is noteworthy that subtypes HLA-B2706 and B2709—found in native Indonesia and Sardinia, respectively—may be partially protective against ReA.

In Norway, an annual incidence of 4.6 cases per 100,000 population for chlamydial ReA and an incidence of 5 cases per 100,000 population for enteric bacteria–induced ReA were reported in 1988-1990. In Finland, nearly 2% of males were found to have ReA after nongonococcal urethritis; the incidence of HLA-B27 is higher in the Finnish population. In the United Kingdom, the incidence of ReA after urethritis is about 0.8%. In the Czech Republic, the annual incidence of ReA in adults during 2002-2003 was reported at 9.3 cases per 100,000 population.

clinical presentation

History

Reactive arthritis (ReA) usually develops 2-4 weeks after a genitourinary (GU) or gastrointestinal (GI) infection (or, possibly, a chlamydial respiratory infection . About 10% of patients do not have a preceding symptomatic infection. The classic triad of symptoms—noninfectious urethritis, arthritis, and conjunctivitis—is found in only one third of patients with ReA and has a sensitivity of 50.6% and a specificity of 98.9%. In postenteric ReA, diarrhea and dysenteric syndrome (usually mild) is commonly followed by the clinical triad in 1-4 weeks.

In a large percentage of ReA cases, conjunctivitis or urethritis occurred weeks before the patient seeks medical attention. Patients may fail to mention this unless specifically asked. Musculoskeletal disease is evident in many of these patients. Vague, seemingly unrelated complaints may obscure this diagnosis at times.

The onset of ReA is usually acute and characterized by malaise, fatigue, and fever. An asymmetrical, predominantly lower-extremity, oligoarthritis is the major presenting symptom. Myalgias may be noted early on. Asymmetric arthralgia and joint stiffness, primarily involving the knees, ankles, and feet (the wrists may be an early target), may be noted. Low-back pain occurs in 50% of patients. Heel pain associated with Achilles enthesopathies and plantar fasciitis is also common.

Both postvenereal and postenteric forms of ReA may manifest initially as nongonococcal urethritis, with frequency, dysuria, urgency, and urethral discharge; this urethritis may be mild or inapparent. Urogenital symptoms, whether resulting from GU infection or from GI infection, are found in 90% of patients with ReA.

An estimated 0.5-1% of cases of urethritis evolve into ReA. Urethritis develops acutely 1-2 weeks after infection through sexual contact and is similar to gonococcal urethritis. A purulent or hemopurulent exudate appears, and the patient complains of dysuria.

In men, chlamydial urethritis is less painful and produces less purulent discharge than acute gonorrhea does, making it difficult to notice. Findings from microscopic examination and cultures can be used to rule out Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection. Coinfection with Chlamydia and Neisseria organisms is common in some areas. In women, urethritis and cervicitis may be mild, with dysuria or slight vaginal discharge, or asymptomatic, which makes diagnosis difficult.

Often, the initial urethritis is treated with antibiotics (especially wide-spectrum tetracyclines or macrolides) when findings suggest gonorrhea. Despite an apparent early cure, the manifestations of the disease appear several weeks later, and the patient may not relate them to a previous episode of urethritis.

Lymphogranuloma venereum infection may be asymptomatic; screening should be considered in all men who have sex with men (MSM) presenting with acute arthritis, particularly if they are infected with HIV.

In addition to conjunctivitis, ophthalmologic symptoms of ReA include erythema, burning, tearing, photophobia, pain, and decreased vision (rare).

Patients may have mild recurrent abdominal complaints after a precipitating episode of diarrhea.

Association with HIV infection

ReA is particularly common in the context of HIV infection. Accordingly, patients with new-onset ReA must be evaluated for HIV. The existing immunodepression in patients with AIDS poses special management problems.

HIV-positive ReA patients are at risk for severe psoriasiform dermatitis, which commonly involves the flexures, scalp, palms, and soles. Frequently, psoriasiform dermatitis is associated with arthritis that involves the distal joints in a destructive pattern. The disturbances of immune homeostasis in AIDS could account for this peculiar expression of psoriasis in these patients.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Risk factors

Certain factors increase your risk of reactive arthritis:

- Age. Reactive arthritis occurs most frequently in adults between the ages of 20 and 40.

- Sex. Women and men are equally likely to develop reactive arthritis in response to foodborne infections. However, men are more likely than are women to develop reactive arthritis in response to sexually transmitted bacteria.

- Hereditary factors. A specific genetic marker has been linked to reactive arthritis. But most people who have this marker never develop the condition.

Prevention

Genetic factors appear to play a role in whether you’re likely to develop reactive arthritis. Though you can’t change your genetic makeup, you can reduce your exposure to the bacteria that may lead to reactive arthritis.

Store your food at proper temperatures and cook it properly. Doing these things help you avoid the many foodborne bacteria that can cause reactive arthritis, including salmonella, shigella, yersinia and campylobacter. Some sexually transmitted infections can trigger reactive arthritis. Use condoms to help lower your risk.

for consultant or book an online appointment- gmail- sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

treatment

Approach Considerations

No curative treatment for reactive arthritis (ReA) exists. Instead, treatment aims at relieving symptoms and is based on symptom severity. Almost two thirds of patients have a self-limited course and need no treatment other than symptomatic and supportive care. As many as 30% of patients develop chronic symptoms, posing a therapeutic challenge.

Physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and intralesional corticosteroids may be helpful for joint, tendon, and fascial inflammation. Low-dose prednisone may be prescribed, but prolonged treatment is not advisable. Antibiotics may be given to treat underlying infection. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as sulfasalazine and methotrexate may be used safely and are often beneficial. No specific surgical treatment is indicated.

Hospitalization of a patient with uncomplicated ReA is not usually indicated. Inpatient care may be considered for patients who are unable to tolerate oral administration of medications, who are unable to ambulate because of significant joint involvement, who have intractable pain, or who have concomitant disease necessitating admission.

Few treatment options exist for HIV-infected patients with severe ReA. Treatment of ReA in the setting of HIV infection poses special problems. However, potentially immunosuppressive therapies (eg, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and psoralen plus ultraviolet A [PUVA]) have been used in some cases, with variable success and relatively few severe complications. A case report from the United Kingdom suggests that antiretroviral therapy may be considered in HIV-infected ReA patients who are unresponsive to standard therapy.

No dietary limitations are necessary unless the patient is receiving steroid therapy. Efforts should be made to maintain joint function with physical activity, joint protection, and suppression of inflammation. Physical therapy may be instituted to avoid muscle wasting and to reduce pain in severe cases. Although no limitations on physical activity need be imposed, symptoms of arthritis will usually limit patients’ activity to some extent.

Pharmacologic Therapy

NSAIDs (eg, indomethacin and naproxen) are the foundation of therapy for ReA. Etretinate/acitretin has been shown to decrease the required dosage of NSAIDs. Sulfasalazine or methotrexate may be used for patients who do not experience relief with NSAIDs after 1 month or who have contraindications to NSAIDs. In addition, sulfasalazine-resistant ReA may be successfully treated with methotrexate.

In a series of 22 pediatric ReA patients from the Republic of China, NSAIDs and sulfasalazine were the mainstays of treatment, with cyclophosphamide used in 14 patients and methotrexate and corticosteroids added in a few. Most achieved full remission within 6 months.

Antibiotic treatment is indicated for cervicitis or urethritis but generally not for postdysenteric ReA. In Chlamydia-induced ReA, some data suggest that prolonged combination antibiotic therapy could be an effective treatment strategy.

Case reports exist that demonstrate the effectiveness of anti−tumor necrosis factor (TNF) medications, such as etanercept and infliximab. No published data are available on the effectiveness of selective cyclooxygenase (COX)–2 inhibitors; however, a COX-2 inhibitor may be tried in patients who do not tolerate NSAIDs and in whom no preexisting contraindication to COX-2 use exists.

Symptom-specific approaches

Arthritis and enthesitis

Joint symptoms are best treated with aspirin or other short-acting and long-acting anti-inflammatory drugs (eg, indomethacin, naproxen). In one report, a patient became asymptomatic after 3 months of aspirin at a dosage of 80 mg/kg/day; the dosage was gradually reduced and eventually discontinued. A combination of NSAIDs is reportedly effective in severe cases. No published data suggest that any NSAID is more effective or less toxic than another (controlled treatment trials are difficult to conduct with an uncommon disease).

Varying success in treating severe cases of ReA with other medications (eg, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, etretinate, ketoconazole, azathioprine, or intra-articular steroid injections) has been reported. In a refractory case or a patient with HIV-associated ReA, the anti−TNF-α agent infliximab may be successful. Depending on the culture results, a short course of antibiotics may be needed; however, treatment may not affect the disease course. Longer-term administration of antibiotics to treat joint symptoms provides no established benefits.

Conjunctivitis and uveitis

Transient and mild conjunctivitis is usually not treated. Mydriatics and cycloplegics (eg, atropine) with topical corticosteroids may be administered in patients with acute anterior uveitis. Patients with recurrent ocular involvement may require systemic corticosteroid therapy and immunomodulators to preserve vision and prevent ocular morbidity.

Urethritis and gastroenteritis

Antibiotics may be considered for urethritis and gastroenteritis, depending on the cultures used and their sensitivity. In general, urethritis may be treated with a 7- to 10-day course of erythromycin or tetracycline. Antibiotic treatment of enteritis is controversial.

Mucocutaneous lesions

Only local care is necessary for mucosal lesions. Topical steroids may be needed for psoriasiform lesions; the use of hydrocortisone or triamcinolone may be beneficial. A topical keratolytic, such as 10% salicylic acid ointment, can be added if needed. Topical salicylic acid and hydrocortisone with oral aspirin has also been suggested.

Hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and salicylic acid 10% ointment are effective in treating chronic keratoderma blennorrhagicum and circinate balanitis, though either condition may heal without medical treatment. Circinate balanitis usually responds to topical steroids; however, it can be recurrent and create a therapeutic challenge. Balanitis refractory to conventional therapy can be successfully treated with the complementary use of topical 0.1% tacrolimus.

Systemic therapy, if required, consists of the administration of oral acitretin, PUVA, methotrexate, cyclosporine, or some combination thereof.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

The choice of a specific NSAID depends on the individual response to treatment. Phenylbutazone may work in patients refractive to other NSAIDs. These agents should be used regularly to achieve a good anti-inflammatory effect. Patients must be instructed on compliance and the possible need to adjust the dosage or switch to another agent. Treatment must be continued for 1 month at maximum dosage before effectiveness can be fully evaluated.

NSAIDs may reduce the intensity and the frequency of recurrences of ocular inflammation and allow a decrease in the corticosteroid dosage, which helps decrease the chances of cataract formation and other associated corticosteroid effects.

The decreased awareness of pain sometimes seen with the use of NSAIDs may alter the patient’s recognition of recurrences. Patients should be examined whenever any change in symptoms occurs to evaluate for recurrence of an acute episode of inflammation. Ocular involvement may parallel systemic and joint disease relapses.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids may be given either via intra-articular injection or as systemic therapy. For ocular manifestations of ReA, they may also be given topically.

Joint injections can produce long-lasting symptomatic improvement and help avoid the use of systemic therapy. Sacroiliac joints can be injected, usually under fluoroscopic guidance.

Systemic corticosteroids may be particularly useful in patients who do not respond well to NSAIDs or who experience adverse effects related to the use of NSAIDs. The starting dose is guided by a patient’s symptoms and objective evidence of inflammation. Prednisone can be used initially at a dosage of 0.5-1 mg/kg/day, tapered according to response.

Topical corticosteroids and mydriatics should be used early and aggressively to reduce tissue damage. Prolonged topical treatment is necessary for several weeks after the inflammation has cleared; early withdrawal of topical corticosteroids frequently results in the return of inflammatory changes. Keratolytics or topical corticosteroids may improve cutaneous lesions. Topical corticosteroids may be useful for iridocyclitis.

Antibiotics

The current view of the pathogenesis of ReA indicates that an infectious agent is the trigger of the disease, but antibiotic treatment does not change the course of the disease, even when a microorganism is isolated. In these cases, antibiotics are used to treat the underlying infection, but specific treatment guidelines for ReA are lacking.

However, in Chlamydia -induced ReA, studies have suggested that appropriate treatment of the acute genitourinary (GU) infection can prevent ReA and that treatment of acute ReA with a 3-month course of tetracycline reduces the duration of illness. Empiric antibiotics may be considered after appropriate cultures have been taken. Nongonococcal urethritis and other infections can be treated specifically with systemic antibiotics. In the absence of contraindications, treatment of urethritis is recommended, even if improvement is not certain.

Although urethritis and cervicitis are commonly treated with antibiotics, diarrhea generally is not. No evidence indicates that antibiotic therapy benefits enteric-related ReA or chronic ReA of any cause.

Long-term antibiotic therapy may be warranted in cases of poststreptococcal ReA; however, this is currently a controversial topic.

Lymecycline (a tetracycline available outside the United States) was studied in a double-blind placebo-controlled study of patients with chronic ReA for a treatment period of 3 months. The duration of illness was significantly shorter in patients with Chlamydia -induced disease than in those with disease triggered by enteric infections.

Azithromycin was shown to be ineffective in a placebo-controlled trial. Nevertheless, in another study, azithromycin or doxycycline in combination with rifampin for 6 months was reported to be significantly superior to placebo and significantly improved symptoms associated with Chlamydia-induced ReA.

Quinolones have been studied because of their broad coverage, but no clear benefit has been reported. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 56 patients with recent-onset ReA, 3 months of treatment with a combination of ofloxacin and roxithromycin was not better than placebo in improving outcomes.

More studies are needed before definite recommendations can be made for the role of antibiotics in the management of ReA.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

In patients who have chronic symptoms or have persistent inflammation despite the use of the agents mentioned above, other second-line drugs may be used. Clinical experience with these DMARDs has been mostly in rheumatoid arthritis and in psoriatic arthritis. However, DMARDs have also been used in ReA, though their disease-modifying effects in this setting are uncertain.

Sulfasalazine has been shown to be beneficial in some patients. The use of this drug in ReA is of interest because of the finding of clinical or subclinical inflammation of the bowel in many patients. Sulfasalazine is more widely used in ankylosing spondylitis. In a 36-week trial of sulfasalazine versus placebo to treat spondyloarthropathies, patients with ReA who were taking sulfasalazine had a 62.3% response rate, compared with a 47.7% rate for the placebo group in peripheral arthritis.

Methotrexate may be used in patients who present with rheumatoidlike disease. Several reports have shown good response, but controlled studies are lacking. Reports also describe the use of azathioprine and bromocriptine in ReA, but again, large studies have not been published. Patients with ReA who have HIV infection or AIDS should not receive methotrexate or other immunosuppressive agents.

Case reports have demonstrated the effectiveness of anti-TNF medications, such as etanercept and infliximab, though there remains a need for randomized, double-blind trials. The high concentrations of TNF-α in the serum and joints of patients with persistent ReA suggest that this cytokine could be targeted in patients who do not respond to NSAIDS and DMARDs. Anti−TNF-α therapy has been demonstrated to be effective treatment for ReA, with a corticosteroid-sparing effect.

However, TNF-α antagonists can increase the risk of serious infection, and it is important to conduct infectious screening and monitoring with a high index of suspicion, as well as preemptive treatment, when such medications are used. Anti-TNF medications can also be associated with severe glomerulonephritis, and it is recommended that renal function be closely monitored in patients treated with these agents.

Interleukin (IL)-6 plays an important role in regulating immune response. Unregulated overproduction of IL-6, however, is pathologically involved in various immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including ReA. Tocilizumab, a humanized anti–IL-6 receptor antibody, may provide clinical benefit in patients who are refractory to conventional therapy or anti-TNF therapy. However, further clinical studies are required.

Surgical Intervention

No surgical therapy for ReA is recommended. However, surgical intervention may be warranted for certain ocular manifestations of the disease.

The posterior spillover of inflammatory material in the chronic iridocyclitis associated with ReA may result in persistent vitreous opacification. The cumulative effects of secondary involvement of the vitreous may result in visually disabling vitreous debris and opacification, making these eyes good candidates for vitrectomy. Although vitrectomy should be considered only after prolonged follow-up care and thorough planning, it appears to offer a definitive improvement in vision in certain cases.

Because of the intense episodes of recurrent inflammation, it is essential to render the eyes as quiet as possible before surgery by using topical, periocular, or systemic corticosteroids. At least 3 months of cell-free slit lamp examinations—6 months for younger patients and severe cases—should be documented before elective surgical intervention.

Preoperative ultrasonography is helpful in determining the degree of vitreous opacification, the thickening of the choroid, and the presence of a cyclitic membrane, which can create significant problems at surgery.

The major objective of surgery in patients with complicated uveitic cataract and vitreous opacification is to improve vision. Vitrectomy may favorably modify the dynamics of the uveitic process, though lensectomy-vitrectomy does not reduce the inflammatory reaction in all cases.

Cystoid macular edema is the major cause of decreased visual acuity after surgery; however, this is a common and serious complication of chronic uveitis even without surgery. Vitrectomy may actually reduce cystoid macular edema with gradual resolution over 1 year and an improvement in vision in some patients.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

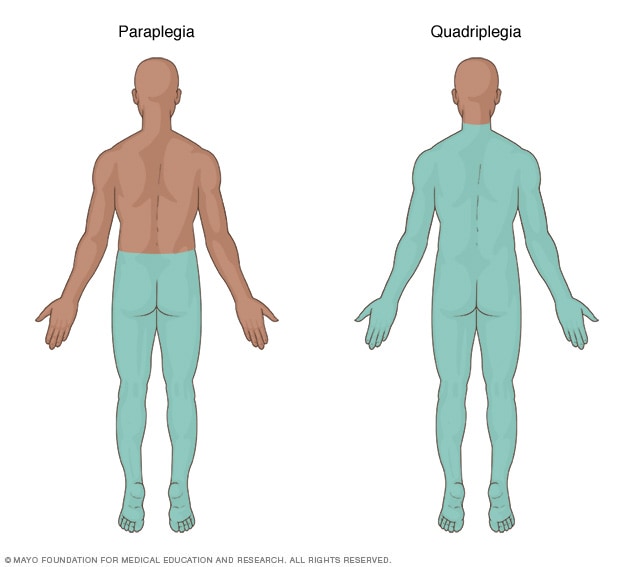

Spinal cord injuriesOpen pop-up dialog box

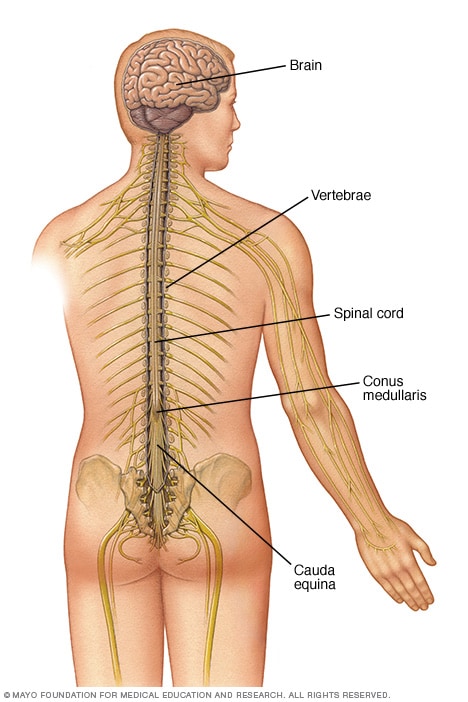

Spinal cord injuriesOpen pop-up dialog box Central nervous systemOpen pop-up dialog box

Central nervous systemOpen pop-up dialog box