REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD) is an idiopathic juvenile avascular necrosis of the femoral head in a skeletally immature patient, i.e. children. Legg-Calvé and Perthes discovered this disease approximately 100 years ago. The disease affects children from ages of two to fourteen. The disease can lead to permanent deformity and premature osteoarthritis

Perthes disease is a rare childhood condition that affects the hip. It occurs when the blood supply to the rounded head of the femur (thighbone) is temporarily disrupted. Without an adequate blood supply, the bone cells die, a process called avascular necrosis.

Although the term “disease” is still used, Perthes is really a complex process of stages that can last several years. As the condition progresses, the weakened bone of the head of the femur (the “ball” of the “ball-and-socket” joint of the hip) gradually begins to collapse. Over time, the blood supply to the head of the femur returns and the bone begins to grow back.

Treatment for Perthes focuses on helping the bone grow back into a more rounded shape that still fits into the socket of the hip joint. This will help the hip joint move normally and prevent hip problems in adulthood.

The long-term prognosis for children with Perthes is good in most cases. After 18 to 24 months of treatment, most children return to daily activities without major limitations.

Description

Perthes disease — also known as Legg-Calve-Perthes, named for the three individual doctors who first described the condition — typically occurs in children who are between 4 and 10 years old. It is five times more common in boys than in girls, however, it is likely to cause more extensive damage to the bone in girls. In 10% to 15% of all cases, both hips are affected.

Epidemiology /Etiology

LCPD is an idiopathic disease, but a variety of theories about the underlying cause have been proposed since its discovery over a century ago, ranging from congenital to environmental and from traumatic to socio-economic causes. LCPD has been associated with thrombosis, fibrinolysis, and abnormal growth patterns of the bone. It has also been associated with an abnormality in the Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Pathway, repeated mircotrauma or mechanical overloading related to hyperactivity of the child or a very low birth weight or short body length at birth.

Some studies suggest a genetic factor, i.e. a type II collagen mutation, and other studies report maternal smoking during pregnancy as well as other prenatal and perinatal risk factors.

It may be be that LCPD requires a set or subset of the aforementioned causes. As of yet it is hard to discern which are determining or merely contributing factors to the onset of the disease.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of osteonecrosis is becoming better understood. Most research suggests either a single infarction event with subsequent mechanical loading that further injures and/or compresses the vessels during the repair process or multiple episodes of infarction are required to produce LCPD.

The key pathological event associated with the initiation of the development of LCPD is disruption of the blood supply to the capital femoral epiphysis. Subsequently ischaemic necrosis occurs in the bone, marrow and cartilage of the femoral head which results in a cessation of endochondral ossification and decreased mechanical strength (fig.2). When mechanical loading surpasses the weakened head’s capacity, deformity is initiated and progresses due to resorption of the necrotic bone and asymmetric restoration of endochondral ossification.

There are four stages in Perthes disease:

- Initial / necrosis. In this stage of the disease, the blood supply to the femoral head is disrupted and bone cells die. The area becomes intensely inflamed and irritated and your child may begin to show signs of the disease, such as a limp or different way of walking. This initial stage may last for several months.

- Fragmentation. Over a period of 1 to 2 years, the body removes the dead bone beneath the articular cartilage and quickly replaces it with an initial, softer bone (“woven bone”). It is during this phase that the bone is in a weaker state and the head of the femur is more likely to collapse into a flatter position.

- Reossification. New, stronger bone develops and begins to take shape in the head of the femur. The reossification stage is often the longest stage of the disease and can last a few years.

- Healed. In this stage, the bone regrowth is complete and the femoral head has reached its final shape. How close the shape is to round will depend on several factors, including the extent of damage that took place during the fragmentation phase, as well as the child’s age at the onset of disease, which affects the potential for bone regrowth.

Cause

The cause of Perthes disease is not known. Some recent studies indicate that there may be a genetic link to the development of Perthes, but more research needs to be conducted.

Symptoms

One of the earliest signs of Perthes is a change in the way your child walks and runs. This is often most apparent during sports activities. Your child may limp, have limited motion, or develop a peculiar running style, all due to irritability within the hip joint. Other common symptoms include:

- Pain in the hip or groin, or in other parts of the leg, such as the thigh or knee (called “referred pain.”).

- Pain that worsens with activity and is relieved with rest.

- Painful muscle spasms that may be caused by irritation around the hip.

Depending upon your child’s activity level, symptoms may come and go over a period of weeks or even months before a doctor visit is considered.

Doctor Examination

After discussing your child’s symptoms and medical history, your doctor will conduct a thorough physical examination.

- Physical examination tests. Your doctor will assess your child’s range of motion in the hip. Perthes typically limits the ability to move the leg away from the body (abduction), and twist the leg toward the inside of the body (internal rotation).

- X-rays. These scans provide pictures of dense structures like bone, and are required to confirm a diagnosis of Perthes. X-rays will show the condition of the bone in the femoral head and help your doctor determine the stage of the disease.

A child with Perthes can expect to have several x-rays taken over the course of treatment, which may be 2 years or longer. As the condition progresses, x-rays often look worse before gradual improvement is seen.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to relieve painful symptoms, protect the shape of the femoral head, and restore normal hip movement. If left untreated, the femoral head can deform and not fit well within the acetabulum, which can lead to further hip problems in adulthood, such as early onset of arthritis.

There are many treatment options for Perthes disease. Your doctor will consider several factors when developing a treatment plan for your child, including:

- Your child’s age. Younger children (age 6 and below) have a greater potential for developing new, healthy bone.

- The degree of damage to the femoral head. If more than 50% of the femoral head has been affected by necrosis, the potential for regrowth without deformity is lower.

- The stage of disease at the time your child is diagnosed. How far along your child is in the disease process affects which treatment options your doctor will recommend.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Observation. For very young children (those 2 to 6 years old) who show few changes in the femoral head on their initial x-rays, the recommended treatment is usually simple observation. Your doctor will regularly monitor your child using x-rays to make sure the regrowth of the femoral head is on track as the disease runs its course.

Anti-inflammatory medications. Painful symptoms are caused by inflammation of the hip joint. Anti-inflammatory medicines, such as ibuprofen, are used to reduce inflammation, and your doctor may recommend them for several months. As your child progresses through the disease stages, your doctor will adjust the dosage or discontinue the medication.

Limiting activity. Avoiding high-impact activities, such as running and jumping, will help relieve pain and protect the femoral head. On occasion, your doctor may also recommend crutches or a walker to prevent your child from putting too much weight on the joint.

Physical therapy exercises. Hip stiffness is common in children with Perthes disease and physical therapy exercises are recommended to help restore hip joint range of motion. These exercises often focus on hip abduction and internal rotation. Parents or other caregivers are often needed to help the child complete the exercises.

- Hip abduction. The child lies on his or her back, keeping knees bent and feet flat. He or she will push the knees out and then squeeze the knees together. Parents should place their hands on the child’s knees to assist with reaching a greater range of motion.

- Hip rotation. With the child on his or her back and legs extended out straight, parents should roll the entire leg inward and outward.

Casting and bracing. If range of motion becomes limited or if x-rays or other image scans indicate that a deformity is developing, a cast or brace may be used to keep the head of the femur in its normal position within the acetabulum.

Petrie casts are two long-leg casts with a bar that hold the legs spread apart in a position similar to the letter “A.” Your doctor will most likely apply the initial Petrie cast in an operating room in order to have access to specific equipment.

- Arthrogram. During the procedure, your doctor will take a series of special x-ray images called arthrograms to see the degree of deformity of the femoral head and to make sure he or she positions the head accurately. In an arthrogram, a small amount of dye is injected into the hip joint to make the shape of the femoral head even easier to see.

- Tenotomy. In some cases, the adductor longus muscle in the groin is very tight and prevents the hip from rotating into the proper position. Your doctor will perform a minor procedure to release this tightness — called a tenotomy — before applying the Petrie casts. During this quick procedure, your doctor uses a thin instrument to make a small incision in the muscle.

After the cast is removed, usually after 4 to 6 weeks, physical therapy exercises are resumed to restore motion in the hips and knees. Your doctor may recommend continued intermittent casting until the hip enters the final stage of the healing process.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Surgical Treatment

Your doctor may recommend surgery to re-establish the proper alignment of the bones of the hip and to keep the head of the femur deep within the acetabulum until healing is complete. Surgery is most often recommended when:

- Your child is older than age 8 at the time of diagnosis. Because the potential for deformity during the reossification stage is greater in older children, preventing damage to femoral head is even more critical.

- More than 50% of the femoral head is damaged. Keeping the femoral head within the rounded acetabulum may help the bone grow into a functional shape.

- Nonsurgical treatment has not kept the hip in correct position for healing.

The most common surgical procedure for treating Perthes disease is an osteotomy. In this type of procedure, the bone is cut and repositioned to keep the femoral head snug within the acetabulum. This alignment is kept in place with screws and plates, which will be removed after the healed stage of the disease.

In many cases, the femur bone is cut to realign the joint. Sometimes, the socket must also be made deeper because the head of the femur has actually enlarged during the healing process and no longer fits snugly within it. After either procedure, the child is usually placed in a cast for several weeks to protect the alignment.

After the cast is removed, physical therapy will be needed to restore muscle strength and range of motion. Crutches or a walker will be necessary to reduce weightbearing on the affected hip. Your doctor will continue to monitor the hip with x-rays through the final stages of healing.

Outcomes

In most cases, the long-term prognosis for children with Perthes is good and they grow into adulthood without further hip problems.

If there is deformity remaining in the shape of the femoral head, there is more potential for future problems; however, if the deformed head still fits into the acetabulum, problems may be avoided. In cases where the deformed head does not fit well into the acetabulum, hip pain or early onset of arthritis is likely in adulthood.

Differential Diagnosis

Listed are some other disorders that should be included in the differential diagnosis for LCPD: All diseases which induce necrosis of the head or those resembling them are questioned in a differential diagnosis[27] :

- Septic arthritis or infectious arthritis: this is an infection of the joint.

- Sickle cell-Osteonecrosis of the hip can be a result of this disease

- Spondyloepiphyseal Dysplasia Tarda: this disease typically affects the spine and the larger more proximal joints

- Gaucher Disease: An autosomal recessive inherited genetic disorder of metabolism in which a dangerous level of a fatty substance called glucocerebroside collects in the liver, spleen, bone marrow, lungs, and at times in the brain

- Transient Synovitis of the hip is a self-limiting condition in which there is an inflammation of the inner lining (the synovium) of the capsule of the hip joint.

- Hip Labral Disorders: The hip labrum is a dense fibrocartilagenous structure, mostly composed of type 1 collagen that is typically between 2-3mm thick that outlines the acetabular socket and attaches to the bony rim of the acetabulum. Hip labral disorders are pathologies of this structure.

- Chondroblastoma: Chondroblastoma refers to a benign bony tumour that is caused by the rapid division of chondroblast cells which are found in the epiphysis of long bones. They have been described as calcified chondromatous giant cell tumours.

- Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis : a chronic inflammatory disorder that occurs before the age 16 and can occur in all races.

- Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia – This is a disorder of cartilage and bone development primarily affecting the ends of the long bones in the arms and legs.

Diagnostic Procedures

A MRI is usually obtained to confirm the diagnosis; however x-rays can also be of use to determine femoral head positioning.

Since LCPD has a variable end result, an imaging modality that can predict outcome at the initial stage of the disease before significant deformity has occurred is ideal.

The extent of femoral head involvement depicted by non-contrast and contrast MRI showed no correlation at the initial stage of LCPD, indicating that they are assessing two different components of the disease process. In the initial stage of LCPD, contrast MRI provided a clearer depiction of the area of involvement.

To quantify femoral head deformity in patients with LCPD novel three dimensional (3D) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reconstruction and volume based analysis can be used. The 3D MRI volume ratio method allows accurate quantification and demonstrated small changes (less than 10 percent) of the femoral head deformity in LCPD. This method may serve as a useful tool to evaluate the effects of treatment on femoral head shape.

Outcome Measures

The questionnaires below can be used to assess the initial function of a person and progress and outcome of operative as well as non-operative treatments. The surveys test the patient on a functional level are useful to provide a baseline and monitor functional progress in the patient’s activities.

- Lower Extremity Functional Scale.

- Harris Hip ScoreThe total score reliability was excellent for physicians (r = 0.94) and physiotherapists (r = 0.95). The physiotherapist and the orthopaedic surgeon showed excellent test–retest reliability in the domains of pain (r = 0.93 and r = 0.98, respectively) and function (r = 0.95 and r = 0.93, respectively). The calculations were done with Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients. The inter-rater correlations were good to excellent (0.74–1.0)

- Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS). The HOOS is suggested to be valuable for younger and more active people due to the subscales.

As for the difference in outcome for non-operative and operative treatments, a meta-analysis performed in 2012 suggests that operative treatment is more likely to yield a spherical congruent femoral head than non-operative methods among six-year-olds or older. For patients who are younger than the age of six, operative and non-operative methods have the same likelihood to yield a good outcome. Children who were six years or older who were treated operatively had the same likelihood of a good radiographic outcome regardless of surgical intervention with a femoral or pelvic procedure. Patients younger than six had a greater benefit from pelvic procedures than femoral procedures.

Examination

Gait

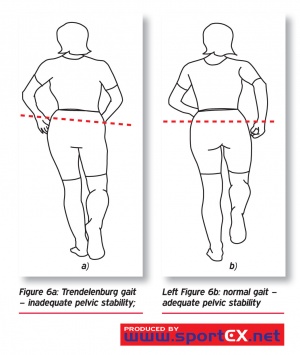

Is usually antalgic. It is possible that the child has a Trendelenburg gait (a positive Trendelenburg sign on the affected side)

The child can also have a Duchenne gait, which is marked by a trunk lean toward the stance limb with the pelvis level or elevated on the unloaded side.

There is insufficient evidence and lack of reliability and validity to support use of the observational gait assessment tools with this population.

Range of movement

The restriction of hip motion is variable in the early stages of the disease. Many patients, may only have a minimal loss of motion at the extremes of internal rotation and abduction. At this stage there usually is no flexion contracture. Loss of hip ROM in patients with early LCPD without intra-articular incongruity is due to pain and muscle spasm. This is why, if the child is examined for instance after a night of bed rest, the range will be much better then later in the day.

Further into the disease process, children with mild disease may maintain a minimal loss of motion at the extremes only and there after regain full mobility. Those with more severe disease will progressively lose motion, in particular abduction and internal rotation. Late cases may have adduction contractures and very limited rotation, but the range of flexion and extension is only seldom compromised.

Pain

Pain occurs during the acute disease. The pain may be located in the groin, anterior hip area, or around the greater trochanter. Referral of pain to the knee is common.

It’s recommended that pain is assessed using the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS).

Atrophy

In most cases there is atrophy of the gluteus, quadriceps and hamstring muscles, depending upon the severity and duration of the disorder.

Medical Management

The approach to treatment is controversial. Prior to evaluating if a surgical intervention is necessary, there has to be a clear understanding of the disease prognosis.

Approaches to treatment can be divided in conservative or operative treatments.

Medications include non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) for pain and/or inflammation.

Psychological factors are also considered. Persons with a history of LCPD are 1.5 times more likely to develop attention deficit disorders compared to their peers. They also have a higher risk of developing depression.

Physical Therapy Management

There is no consensus concerning the possible benefits of physiotherapy in LCPD, or in which phase of the development of the health problem it should be used.

Some studies mention physiotherapy as a pre- and/or postoperative intervention, while others consider it a form of conservative treatment associated with other treatments, such as skeletal traction, orthesis, and plaster cast.

In studies comparing different treatments, physiotherapy was applied in children with a mild course of the disease. The characteristics of the patients were:

- Children with less than 50% femoral head necrosis (Catterall groups 1 or 2)

- Children with more than 50% femoral head necrosis, under six years, whose femoral head cover is good (>80%)

- Herring type A or B

- Salter Thompson type A

For patients with a mild course, physiotherapy can produce improvement in articular range of motion, muscular strength and articular dysfunction. The physiotherapeutic treatment included:

- Passive mobilisations for musculature stretching of the involved hip.

- Straight leg raise exercises, to strengthen the musculature of the hip involved for the flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction of muscles of the hip.

- They started with isometric exercises and after eight session, isotonic exercises.

- A balance training initially on stable terrain, and later on unstable terrain.

For children over 6 years at diagnosis with more than 50% of femoral head necrosis, proximal femoral varus osteotomy gave a significantly better outcome than orthosis and physiotherapy.

There is an evidence-based care guideline concerning post-operative management of LCPD in children for age 3 to 12 and an evidence-based care guideline for conservative management of LCPD in children age 3 to 12. These studies are mostly based on ‘local consensus’ of the members of the LCPD team from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. These guidelines express the evidence regarding physical therapy (PT) treatment pathways, post-operatively and conservative management (see appendix 3 about evidence levels) . The following recommendations are made:

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com

Conservative management

Physical therapy interventions have been shown to improve ROM and strength in this patient population (3).

Individuals who participate in supervised clinic visits demonstrate greater improvement in muscle strength, functional mobility, gait speed, and quality of exercise performance than those who receive a home exercise program alone or no instruction at all (2).

Individuals who receive regular positive feedback from a physical therapist are more likely to be compliant with a supplemental home exercise program. (4)

It is recommended that supervised physical therapy is supplemented with a customized written home exercise program in all phases of rehabilitation. (2)

Improve ROM: (see appendix 1 for exercise prescription)

- Static stretch for lower extremity musculature (2)

- Dynamic ROM (2)

- Perform AROM and AAROM (active assistive range of motion) following passive stretching to maintain newly gained ROM (2)

Improve strength:

- Begin with isometric exercise and progress to isotonic exercises in a gravity lessened position with further progression to isotonic exercises against gravity. It is appropriate to include concentric and eccentric contractions (3).

- Begin with 2 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions of each exercise (2), with progression to 3 sets of each exercise to be used (2)

- Local consensus would also do exercises to improve balance and gait and interventions to reduce pain.

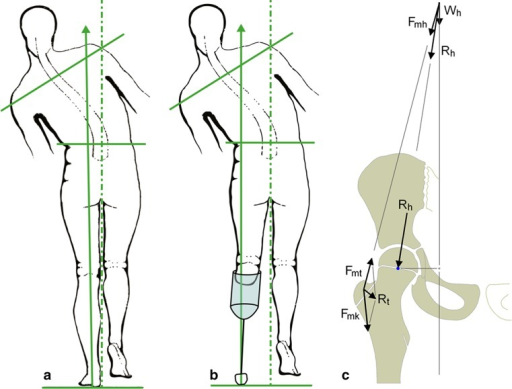

The hip overloading pattern should be avoided in children with LCPD. Gait training to unload the hip might become an integral component of conservative treatment in children with LCPD.

Non-surgical treatment with a brace is a reliable alternative to surgical treatment in LCPD between 6 and 8 years of age at onset with Herring B involvement. However, they could not know whether the good results were influenced by the brace or stemmed from having good prognosis of these patients.

Post-operative management

The rehabilitation is described with reference to the various stages of rehabilitation.

- Initial Phase (0-2 weeks post-cast removal)

Goals of the Initial Phase

- Minimize pain

- Hot pack for relaxation and pain management with stretching (2)

- Cryotherapy (5)

- Medication for pain (5)

- Optimize ROM of hip, knee and ankle (see appendix 1 for exercises)

- Passive static stretch (2) (A hot pack may be used, based on patient preference and comfort (2))

- Dynamic ROM (2)

- Perform AROM and AAROM following passive stretching to maintain newly gained ROM (2)

- Increase strength for hip flexion, abduction, and extension and knee and ankle (see appendix 2 for exercises)

- Begin with isometric exercises at the hip and progress to isotonic exercises in a gravity lessened position (3)

- Begin with isometric exercises at the knee and ankle, progressing to isotonic exercises in a gravity lessened position with further progression to isotonic exercises against gravity (3)

- Begin with 2 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions of each exercise with progression to 3 sets of each exercise to be used (2)

- Improve gait and functional mobility

- Follow the referring physician’s guidelines for WB status (5)

- Transfer training and bed mobility to maximize independence with ADL’s (5)

- Gait training with the appropriate assistive device, focusing on safety and independence (5).

- Improving skin integrity

- Scar massage and desensitization to minimize adhesions (5)

- Warm bath to improve skin integrity following cast removal, if feasible in the home environment (5)

- Warm whirlpool may be utilized if the patient is unable to safely utilize a warm bath for skin integrity management (5)

PT is supervised at a frequency of 2-3 time per week (weekly) (5)

- Intermediate Phase (2-6 weeks post-cast removal)

Goals of the Intermediate Phase

- Minimize pain (see ‘initial phase’)

- Normalize ROM of the knee and ankle and optimize ROM of hip in all directions

- See ‘initial phase’ and see appendix 1 for exercises

- Increase strength of the knee and hip (see appendix 2 for exercises)

- Isotonic exercises of the hip in gravity lessened positions and advancing to against gravity positions (3)

- Isotonic exercises of the knee and ankle in gravity lessened and against gravity positions (3)

- Maintain independence with functional mobility maintaining WB status and use of appropriate assistive devices (5)

- Improving gait and functional mobility (5)

- Follow the referring physician’s guidelines for WB status (5)

- Continue gait training with the appropriate assistive device focusing on safety and independence (5)

- Begin slow walking in chest deep pool water with arms submerged (5)

- Improving Skin Integrity

- Continue with scar massage and desensitization (5)

PT is supervised at a frequency of 2-3 time per week (weekly) (5)

It is recommended that activities outside of PT are restricted at this time due to WB status. If the referring physician allows, swimming is permitted (5)

- Advanced Phase (6-12 weeks post-cast removal)

Goals

- Minimize pain (see ‘initial phase’)

- optimize ROM and flexibility of the hip, knee, and ankle

- see ‘initial phase’ and see appendix 1 for exercises

- Increase strength of the knee and hip, except for hip abductors, to at least 70% of the uninvolved lower extremity and increase strength of the hip abductors to at least 60% of the uninvolved lower extremity due to mechanical disadvantage (4 + 5) (see appendix 2 for exercises)

- Isotonic exercises of the hip, knee, and ankle in gravity lessened and against gravity positions, including concentric and eccentric contractions (3)

- WB and non-weight bearing (NWB) activities can be used in combination based on the patient’s ability (4) and goals of the treatment session (5)

- Begin upper extremity supported functional dynamic single limb activities (e.g. step ups, side steps) (5)

- Continue with double limb closed chain exercises with resistance, progressing to single limb closed chain exercises with light resistance if WB status allows (5)

- Use of a stationary bike in an upright or recumbent position keeping the hip in less than 90 degrees of flexion (5)

- Ambulation without use of an assistive device or pain (5)

- Negotiate stairs independently using step to pattern with upper extremity (UE) support (5)

- Improve balance to greater than 69% of the maximum Pediatric Balance Score (39/56) or single limb stance of the uninvolved side (5)

- Improving gait and functional mobility (5)

PT is supervised at a frequency of 1-2 time per week (weekly) (5)

It is recommended that activities outside of PT are limited to swimming if the referring physician allows (5).

Note: Running and jumping activities are restricted at this time (5).

- Pre-Functional Phase (12 weeks to 1+ year post-cast removal)

Goals

- Minimize pain (see ‘initial phase’)

- Optimize ROM and flexibility of the hip, knee, and ankle

- Static stretch (2)

- Increase strength of the knee and hip, except for hip abductors, to at least 80% of the uninvolved lower extremity and increase strength of the hip abductors to at least 75% of the uninvolved lower extremity due to mechanical disadvantage (4 + 5)

- see ‘advanced phase’ and see appendix 1 for exercises

- Negotiate stairs independently with reciprocal pattern an upper extremity support (5)

- Improve balance to 80% or greater of the maximum Pediatric Balance Score (at least 45/56) or single limb stance of the uninvolved side (5)

- Non-painful gait pattern with minimal deficits and normal efficiency (5)

PT is supervised at a frequency of 1-2 time per week (weekly) (5)

It is recommended that activities outside of PT include swimming and bike riding as guided by the referring physician (5).

Note: Running and jumping activities are restricted at this time (5).

- Functional phase

Goals

- Reduce pain to 1/10 or less (see ‘initial phase’)

- Normalizing ROM: Increase ROM to 90% or greater of the uninvolved side for the hip, knee, and ankle, except for hip abduction (5) and Increase hip abduction ROM to 80% or greater due to potential bony block (4)

- Static stretch (2)

- Normalizing strength: Increase strength of the knee and hip, except for hip abductors, to 90% or greater of the uninvolved lower extremity (5) and Increase strength of the hip abductors to at least 85% of the uninvolved lower extremity due to mechanical disadvantage (4+5)

- Progress isotonic exercises of the hip, knee, and ankle and include concentric and eccentric contractions (3).

- WB and NWB activities used in combination based on the patient’s ability (4) and goals of the treatment session.

- Functional dynamic single limb activities (e.g. step ups, side steps) with upper extremity support as needed for patient safety (5)

- Progress single leg closed chain exercises with resistance (4)

- Use of a stationary bike in an upright or recumbent position keeping the hip in less than 90 degrees of flexion

- Ambulation with a non-painful limp and normal efficiency (5)

- Negotiation of stairs independently using a reciprocal pattern without UE support (5)

- Improve balance to 90% or greater of the maximum score on the Pediatric Balance Scale (at least 51/56) or single limb stance of the uninvolved side (5) It is recommended that progression to the Functional Phase occur when the physician has determined there is sufficient re-ossification of the femoral head based on radiographs (5). Note: Jumping and other impact activities are still limited and only progressed per instruction from the physician based on healing and progression of the disease process

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT OR BOOK A CONSULANT – Sargam.dange.18@gmail.com